Christian Hermeticism for Dummies

Some thoughts on some guys with too much time on their hands ripping on Sebastian Morello’s new book

For some reason, I got dragged into a TradCath/Orthobro black hole of shallow thinking and character assassination last week when not one, but two (three counting Paul Kingsnorth’s acerbic yet pithy diatribe in a Substack note) polemics about my friend Sebastian Morello’s newest book Mysticism, Magic, and Monasteries. One, by a Michael Warren Davis (with whom I was not previously familiar), “The Conservative Case for Antichrist,” is one hot mess of an article which made me wonder if he were writing about the same book I had read. I’m still not sure he is. The other article, entitled “Occult subversion of traditional Catholicism,” is by Catholic Defensor Fidei Thomas V. Mirus (never heard of him either), who accuses Sebastian of black magic among other things. He also maligns me as “heterodox” (I was, like, “So?”), shade he also throws at David Bentley Hart and John Milbank no less. The BIG GUNS came out this week, people.

When all this erupted, I joked on social media that “If Orthobros and Militant Catholics had any power, I’d be tied to a post on a pile of smoldering faggots.” Of course, X’s AI interpreted that as a slur against homosexuals (picture that visual with my original statement) and flagged it as “hate speech.” Imagine how bundles of sticks would feel! Speaking of bundles of sticks, the pseudonymous Catholic trad man about town who goes by the name “Alistair McFadden” also jumped into the fray (I felt like making the sign of cross at him, praying Psalm 67, and commanding, “Tell me your name!”) For me, it was like an Orthobro/TradCath hattrick. I linked their articles so you can read them for yourself, as I don’t plan on writing a refutation (it wouldn’t be worth it). My intention here is to come to terms.

It was clear to me from reading their articles, that, not only were they wrong about Sebastian’s book (he wrote a rebuttal that is worth reading here), but that they have absolutely no idea of what Hermeticism, let alone Christian Hermeticism is.

Now, it’s not surprising that they don’t know what Hermeticism (either one) is, because most people don’t. But I do. I don’t say that as a boast, but only because I wrote my doctoral dissertation on figures who have been painted with a “Hermetick brush,” as it were. My dissertation was later published as Literature and the Encounter with God in Post-Reformation England (I had a cooler title, but the publisher was dull and unimaginative), and there I argue thusly:

“As it has come down to us, ‘hermetic philosophy’ is a catch-all phrase for a plethora of more or less or less heterodox [there’s that word again!] ideas, including alchemy, magic, Kabbalah, and astrology as well as Neoplatonism and Hermeticism proper…. Unfortunately, this imprecise descriptive has become almost universally accepted, even in contemporary scholarship.”

Then I point to a representative quote from the great scholar Stanton Linden regarding the use of the term hermeticism when applied to the poetry of Henry Vaughan: “I do not mean that Vaughan necessarily subscribed to the ideas and doctrines from the Corpus Hermeticum that appear in it or that, as such, they were a dominant part of his religious creed…. Vaughan, I think, saw no fundamental incompatibility or contradiction between his borrowings and the more traditional Christianity he espouses in many of the poems of Silex Scintillans.” And Vaughan’s is a traditional Christianity, indeed. But “Hermeticism” and “Christian Hermeticism” are by no means univocal terms.

I remember when defending my dissertation and one of my examiners asked why I chose so many “weird” people to write on (John Dee, John Donne, Sir Kenelm Digby and Thomas and Henry Vaughan, and Jane Lead). I answered, “Well, they might be weird to us. But in their own time, they would have described themselves as something like traditionalists, especially Digby and the Vaughans, as they thought they were preserving the traditional view of the Two Books (the Bible and Creation), the microcosm and the macrocosm, the reality of heaven and angels, etc., in the face of the encroaching materialism of the Cartesian and Baconian revolutions then ascendant.”

As many of my readers and those familiar with my thoughts from video and interviews will know, I think definitions are only useful up to a point—and the gentlemen writing about Sebastian’s book are stuck on very narrow definitions that seem to be taken from an unreflective and reactive nun teaching seventh grade or the kinds of Protestants who think playing UNO when you’re seven leads to a life of gambling, fornication, and debauchery.

Since I have written books on these things (Hermeticism and so forth—not gambling, fornication, and debauchery), I won’t rehash all of what is there in this space. But I will try to give a short historical overview.

The Renaissance through the Seventeenth Century

The so-called “Christian Hermeticism” pervasive in the Florentine Renaissance in figures like Pico della Mirandola and Marsilio Ficino was thoroughly Christian, idealistic, and full of hope. Without it, the sublimity of the art of Michelangelo and Raphael would be unimaginable (Michelangelo knew both at the Plato Academy under the patronage of Lorenzo di Medici). Unfortunately, the shadow side of this hopeful theology/philosophy showed itself in the fire and brimstone first of Savonarola and then the Protestant Reformations (in particular with the party-poopers coming out of Calvinism—the guys who outlawed Christmas). Savonarola actually got to Pico and drove him mad (cult leaders do that). Savonarola was not long after condemned as a heretic and schismatic, hanged, and his body burned to ash. Stuff like that.

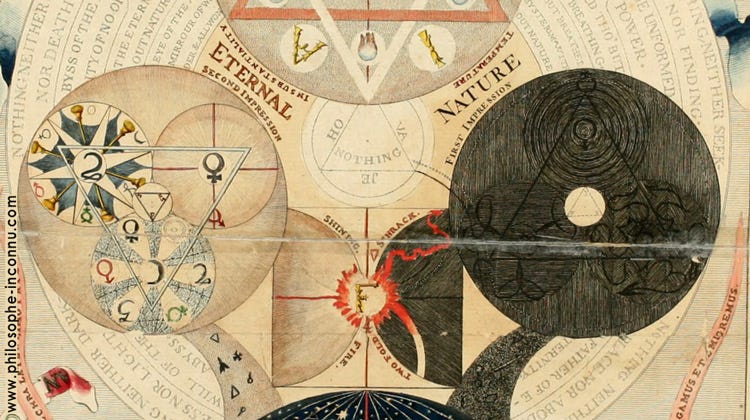

The “Christian Hermeticism” description, while not perfect, is important to the Florentine Renaissance—because they were pretty much the first to read the Corpus Hermeticum in early modernity. It set them on fire. Some of them even saw Hermes Trismegistus as a precursor to Moses and someone nearly a saint, as so many (but not all, obviously) of his teachings, like those of Plotinus, are congruent with Christian faith. He was part of the Prisca theologia, the “the pristine theology,” or so they thought. (Turns out, the Hermetica was more contemporary of Neoplatonism than anyone had thought). So great was the enthusiasm for the Corpus Hermeticum (and it really is worth reading) that a fifteenth century mosaic of him adorns the floor of the Cathedral of Siena.

(Did you hear that? It may have been Orthobro/TradCath heads exploding.)

Often the Christian Hermeticism of the Florentine Renaissance gets conflated with the more magical side of Neoplatonism (especially with Iamblichus’s On the Mysteries), but magical Neoplatonism and Hermeticism (and figures from the period certainly read them both), are not by any means identical. Any careful scholar would know that. But Davis and Mirus are neither careful nor scholars. They’re guys with a platform and an agenda. That’s all you need these days.

Jumping forward to the late-sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, we come to what might be termed “Christian Hermeticism’s last stand” (though it really wasn’t) as figures like Henry Vaughan and his twin brother, the Anglican priest and alchemist, Thomas; the Paracelsian physician and philosopher Robert Fludd; the alchemist, polymath, and Catholic apologist Kenelm Digby; the physician and philosopher Michael Maier, and others held on to the last vestiges (or what seemed to be the last vestiges) of a traditional Christian metaphysic. For them, the world of the spirit and the world available to our senses were not alien, but polarities of one integral whole. It doesn’t get any more Christian than that. What was different with them, though, is that they tried to prove this scientifically (and alchemy, astrology, and magic were scientific disciplines going back to the ancients). You’d think Davis and Mirus (even Kingsnorth) would like this kind of thing. Being charitable, I would assume they probably don’t know about it.

Modernity

Following the rise of the Scientific Revolution and then the Enlightenment, what we can call “Christian Hermeticism” went underground into what my friend John Milbank calls “the alternative modernity.” Later it made appearances in Goethe, in German Romanticism, and in Idealism and even later in what has been called the “Occult Revival” of the nineteenth century. Especially in France, the Occult Revival often possessed decidedly Catholic elements and was in part developed by practicing Catholics, most notably Éliphas Lévi (who had been ordained a deacon, though left the path to the priesthood a week before his scheduled ordination) and the novelist and impresario of the Salon Rose+Croix, the flamboyant Joséphin Péladan—neither of whom was ever condemned or censored by the Catholic Church. In fact, Lévi routinely submitted his work to the ecclesial authorities (who described it as “extravagant,” though stopped short of condemnation). This was certainly, especially in the case of Lévi, a magical enterprise so I get while people might be nervous about his work (with Péladan it was more aesthetic). Nevertheless, his book Transcendental Magic is an enormously important text, as in it, among other things, he explains (drawing on Plotinus) how what we now call “propaganda” is through and through a magical operation, relying, as it does, on, among other things words and images. (I’ve written about this quite a bit). Also, while still a cleric, he wrote an extraordinary book on the Virgin Mary, La Mère de Diu (1844), which, unfortunately, has yet to be translated into English.

One thing Lévi and Péladan were doing, however one might judge their efforts or results, was standing against the materialist, physicalist, atheistic, and mechanistic hegemony of their times (and ours). Essentially, they were telling their foolish times, “There are more things both in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” Words that still obtain.

Valentin Tomberg and Meditations on the Tarot

The term “Christian Hermeticism” owes much of its cultural currency to the popularity of the book Meditations on the Tarot, first published in French and German editions before its English translation by Robert Powell appeared in 1985. The subtitle of the book is “A Journey into Christian Hermeticism.” It was published anonymously and posthumously, but the secret was not very well-kept that it was the work of the Russian esotericist and convert to Catholicism, Valentin Tomberg. I first read the book in my twenties, soon after it was published—and it blew me away. I had grown pretty disenchanted with the disenchanted post-Vatican II Catholicism of my childhood and youth, but Tomberg’s book made me think twice about throwing the Catholic baby out with the Vatican II bathwater. The book has many devoted followers—and not a few detractors. Both lovers and detractors have grounds for their opinions (which I won’t delve into here). Germane to our discussion of the recent criticism of Sebastian’s book, the crux of the issue is Tomberg’s embrace of what he calls “Sacred Magic” as part of what he identifies as the path of Christian Hermeticism. Sebastian is a big Tomberg guy (which clearly galls Messrs. Davis and Mirus). Tout court: Sacred Magic is not the province of a magician; it’s under the aegis of Catholic tradition, rooted in the apostolic traditions and formulas of Catholic praxis and liturgy. Sacred Magic has nothing to do with cartomancy, ceremonial paraphernalia, or anything sketchy like that. Basically, its weapons are faith in Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary, the words of the liturgy and scripture, and the signs, seals, and gestures of the Catholic (and Orthodox) patrimony. Sacred magic for Tomberg is found in the sign of the cross, the rosary, the sacramentals (such holy water or chrism) and the Sacraments. One of the earliest criticisms of Catholicism from some early Protestants was precisely on the grounds that what Catholics do in both liturgical and lay practice is magic or performance. So, in a sense, both Davis and Mirus are Protestants. Maybe they don’t like the word “magic.” So what. Things we don’t know about often frighten us.

I hope that clears things up a little. But it probably won’t. People are like that.

'For them, the world of the spirit and the world available to our senses were not alien, but polarities of one integral whole. It doesn’t get any more Christian than that. What was different with them, though, is that they tried to prove this scientifically (and alchemy, astrology, and magic were scientific disciplines going back to the ancients). You’d think Davis and Mirus (even Kingsnorth) would like this kind of thing. Being charitable, I would assume they probably don’t know about it.'

I always appreciate charity!

I studied Hermeticism myself back in my Wiccan days. The mythical Hermes is very much admired by the witches, of course. I read the Corpus, and indeed 'Meditations on the Tarot.' I loved my tarot cards back in the day. I got rid of them all when I became a Christian, as advised, and I don't regret it.

What's interesting to me about this discourse is how Western it is. You write yourself here about the difficulty, or impossibility, of finding 'mysticism' in the post-Vatican 2 Catholic church. This is essentially why I became Orthodox - well, that and the fact that I felt it was where I was led in prayer. You joke that 'Orthobros' would be horrified by the Hermeticist mosaic in the Sienna Cathedral. Actually I think it would make them smirk. That's a Catholic mosaic, after all.

Much of this search for so-called 're-enchantment' in the West is a search for something that was once probably here but seems to have fled. Where is the Christianity of John of the Cross and Teresa of Avila and the author of the Cloud of Unknowing in the Christianity of the West today? Maybe it is hiding, but I couldn't find it. In the Orthodox Church, for all of its faults, this strain is still central. To say that is not to be an 'Orthobro' who wants a theological dog-fight. That's almost the opposite of the correct response.

I'm hoping that Orthodoxy can help return a genuine Christian mysticism to a parched West, so that we don't need to turn to tarot cards or the Kabbalah for what we are stumblingly seeking. We'll see, I suppose.

This is the result of christianity losing its 'totalitarian' position in the Western world. It now purity spirals because it has merely become an optional position among many, many others.

Badly understood, adherents now wonder why they would cater to the odd ducks, while their turf is perceived as being under attack. Why would this weirdo align with my personal optional position if he doesn't adhere exactly to every dogmatic proposition it states? "Aren't there other places you should be?" people wonder.

If it still were all-encompassing, it should cater to the odd balls, the weird, the marginal, the erratic, the eccentric, otherwise it wouldn't be all-encompassing. It no longer is all-encompassing. It has been repurposed as a scaffold and wall to protect 'the normal' against the deconstruction.

At the end of the day; the collapse of cosmology that took place in modernity has people clinging to any flotsam they can get a hold on to keep their head above water; politics, identity, rainbowflags, religion, popculture, some kinetic conflict far away. Whatever keeps them from getting washed away in the ocean of meaningless nihilism or total aporiatic chaos. Thus whatever their flotsam of chose is, it has become a lifeline to be defended at all cost. It can't be shared with the erratic, otherwise the flotsam will also turn out to be little more than dust.