Yesterday I found a wonderful surprise in my rural mailbox: a copy of Guido Preparata’s Empire & Church: Anglo-America’s Buyout of the Vatican and the Hyper-Modern Demise of Catholicism. Guido, who’s been a guest on the Regeneration Podcast at least four times, asked me to write a foreword for his book a couple of years ago, which I was more than happy to do. In the meantime, life moved along. Guido and his family moved from California to Italy, which moved the release of the book back, and I, as usual, was busy with my farm and many other projects. So, when I read my foreword yesterday, I surprised myself. Actually, I’d forgotten what I wrote, but was nevertheless pleased that what I did write aged pretty well. In fact, it seems even more relevant now than when I sent it to Guido in July of 2022.

I first encountered the work of my friend Guido, an economist and historian who has taught at the Gregorian University in Rome, at least ten years ago when I was interested to see if anyone was writing about perishable currency, an idea Rudolf Steiner supported in the wake of World War I, and was pleased to find some articles by Guido published in Anarchist Studies. Then, when I met my now podcast partner Mike Sauter and he came to a conference I held at my farm in 2016, I discovered that he, too, knew about Guido’s work and that he had even corresponded with him. Thus a ring of co-conspirators was born. I later used the thoughts of Guido in my chapter on alternate economies—“Oikonomia: The Household of Things”— included in my book Transfiguration.

Church & Empire is an important book, and I am honored to have my name associated with it—but I probably just ruined my chances for a papal audience.

FOREWORD

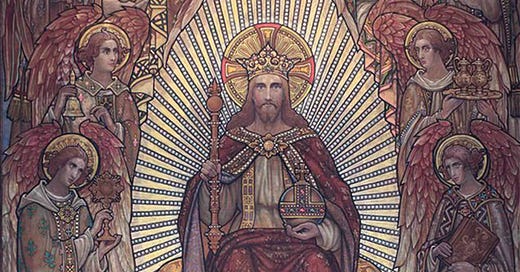

In June of 2022 the Vatican issued a 20 euro coin commemorating the miracle of the COVID vaccines. The issuance of this coin may be one of the most emblematic gestures of our times, gathering together, as it does, the constellation of financial, governmental, and corporate power wedded to a vestigial, albeit anemic, spiritual authority. Indeed, in one transactional signifier the worldly and religious powers unite, foreshadowing the impending arrival a new Christendom: a Christendom, albeit, devoid of Christianity though maintaining the residual symbolic power of the tenuously reconciled emperor and pope. This phenomenon in no way realizes Jacques Derrida’s imagination of “a religion without religion,” as ethics, morality, or spirituality have a very limited, one might say “ceremonial,” role in such a federation, though the palimpsest of Jesuit power married to Templar banking ingenuity indeed bleeds through the Vatican’s legal tender. The real game here, that is, is the game of empire and the usual historical players all hold their usual places at the table, though none of them is so foolish as to risk calling it an empire in public.

This empire, it is only too plain to see once one looks behind the curtain, belongs to what Guido Preparata in this book deems “the Great Commonwealth”: British banking savvy and avarice married to American military strength and lust for prominence. This empire, as it so happens, on its own has all it needs save for one thing: the appearance of holiness. As Preparata writes, “Anglo-American imperialism is but a vulgar and artificial surrogate of the ancient, ‘sacred and spiritual’ Imperium.” This is the imperium of our time, for “America pursues a foreign, imperial policy that has been, from the outset, Britain’s” so the power of the Catholic Church is called upon to provide sacerdotal cover for imperial lust, though empire and Church have an enormously complicated relationship. To aid in this regard, American Neocons—from Norman Podhoretz and Richard John Neuhaus to Michael Novak and George Weigel—have wittingly or unwittingly employed a strategy that is “virtually identical to that of all imperialist factions, which, throughout the ages, have striven to bend the Holy See into the ancillary role of a mere consecratory office of the imperial executive.” Receive the Eucharist on Sunday, that is, but feel free bomb Iraq (or arm Ukraine) on Monday. Thus empire.

What we see in the imperium Preparata sketches for us in these pages, then, is a grotesque inversion of the myth of Christendom, which suggests why the Catholic Church is still a significant player in its promotion and rituals. This iteration of Christendom is by no means what Novalis had in mind when he wrote Europa [Die Christenheit oder Europa] (1799). Though he fully recognized that “The old Papacy lies in its grave and Rome for a second time has become a ruin”—words especially timely now—Novalis still maintained the hope for a regenerated Europe (to which we can now include the Americas) in which “Christendom must come alive again and be effective, and, without regard to national boundaries, again form a visible Church which will take into its bosom all souls athirst for the supernatural, and willingly become the mediatrix between the old world and the new.” The Techno-Structure—consisting of the World Economic Forum in concert with its many visible and invisible partners—clearly holds to a diabolical caricature of Novalis’s integralism here, though one shorn of the supernatural, of conviviality, and of any manner of commitment to the common good, though marketed under the puerile slogans of “concern,” “safety,” and “sustainability.” And, as Preparata argues, the Techno-Structure still needs the pious symbolism of the Catholic Church to achieve its desired objective. Certainly a mad proposal.

Such madness in the course of human events is nothing new. There seems to be a lust for empire that runs deep in the human psyche—especially when humanity is arranged into collectives. Surely, the ancient Israelites gave evidence of this as they clamored to the judge Samuel to require God to give them a king. The answer they received was probably not what they were counting on:

He will draft your sons, make them serve on his chariots and horses, and make them run ahead of his chariots. He will appoint them to be his officers over 1,000 or over 50 soldiers, to plow his ground and harvest his crops, and to make weapons and equipment for his chariots. He will take your daughters and have them make perfumes, cook, and bake. He will take the best of your fields, vineyards, and olive orchards and give them to his officials. He will take a tenth of your grain and wine and give it to his aids and officials. He will take your male and female slaves, your best cattle, and your donkeys for his own use. He will take a tenth of your flocks. In addition, you will be his slaves. When that day comes, you will cry out because of the king whom you have chosen for yourselves. The Lord will not answer you when that day comes. (1 Samuel 8:11-18)

But even the powerful rhetorical skills of the Lord of Hosts weren’t enough to persuade the Israelites. They wanted a king; and they got one. And they were not answered when the day of their remorse came.

The Techno-Structure Preparata interrogates in this book capitalizes (note the metaphor) on the subconscious lust for a king, now amplified to the lust for an emperor, however unarticulated, however denied. The emperor of the Techno-Structure, indeed, is an invisible one who nevertheless promises that we will “own nothing and be happy” through his minions: governments, corporation, NGOs, and mass media.

The Techno-Structure is well aware that no one would consciously choose a life of servitude and surveillance, a life of pointlessness and existential despair, so instead it promotes what Huxley predicted so accurately: the mollifications of pharmacology, entertainment, and the relentless consumerism that attend the Novus Ordo in Saecula Saeculorum. “Let’s face it,” writes Preparata, “Anglo-America makes fascism fun.” The Catholic Church, as Preparata shows, aids and abets this project with the tattered rags of a lost holiness—and Huxley’s parodic Arch-Community Songster seems less and less comedic and more and more a tragic reality. But who am I to judge?

The problem, as always, is that the corporate and bureaucratic structure that is the Catholic Church is by no means identical with the universal church (what some Protestant reformers once called “the Invisible Church”); and, for Catholics at least, the two seem to be ineradicably conflated. The only result, then, can be some kind of fascism. As Preparata argues, “As for the Catholics, either progressive or conservative, they, too, are fascist, for, ultimately, what they worship is not Christ but the structural, corporate might of the Church—or, rather, nostalgically, what it once was.”

Indeed, to conflate worldly and spiritual powers is the gravest of category mistakes. But this is nothing new. In the seventeenth century, the Anglican divine and poet Thomas Traherne identified the problem with great perspicuity:

“To Contemn the World, and to Enjoy the World, are Things contrary to each other. How then can we contemn the World which we are Born to Enjoy? Truly there are two Worlds. One made by God, the other by Men. That made by GOD, was Great and Beautiful. Before the Fall, It was Adams Joy, and the Temple of his Glory. That made by men is a Babel of Confusions: Invented Riches, Pomps and Vanities, brought in by Sin. Giv all (saith Thomas a Kempis) for all. Leav the one that you may enjoy the other.”

Is there a better description not only of our political condition but even of the Catholic Church? I think not. The rage that underpins Preparata’s condemnations in this book—in true jeremiad fashion—is not so much born of a dissatisfaction in the conditions of this our exile, but that he, like Traherne, sees more clearly than most the Real that shines through even the morass of corruption and decay with which we are so tragically embedded.

Yet the narrative Preparata unfolds here is not one of hope.

Nevertheless, he himself is not without hope. In his conclusion to the first of the essays here, Preparata alludes to an alternative to the Techno-Structure: “Our ‘third way,’ which clearly acknowledges national difference as a source of creative union among forces from all corners of the world will have to rally, organize itself territorially, study new ways to reform the economy through cooperation, and, hopefully, proceed to confederate this constellation of free-districts in the name of pacifism.” It is my hope that Preparata will follow this with another book describing in detail this third way. For it is a future that I, too, work toward.

The French philosopher and mystic Simone Weil once wrote that “Truth is too dangerous to touch. It is an explosive,” and her words have never born such import as they do when confronted with this book by Guido Preparata. For the truth he reveals is, indeed, too dangerous to touch. But we need to risk injury, nevertheless.

Michael Martin

11 July 2022

The quibbles I have with this essay pale in comparison with my overflowing admiration for, and enthusiastic agreement with it. I will say, though, with regard to the Church's "lost holiness", that the Church still has all the holiness it ever had: the holiness of the saints and artists, canonized, ignored or anathematized, who live in the Spirit of Christ. The rest of it has always been, remains, and always will be a blasphemy and a farce.

Oh man, that was awesome! The whole thing, but I just about jumped out of my chair for joy when you dropped the beautiful atom bomb of 1 Sam 8 on the whole thing -- I love it when people do that, and it happens too rarely. Have you read Jacques Ellul's "Subversion of Christianity"? That is a book that I try, but fail, to get people to read and talk about with me. If 1 Sam 8 is your jam (I call this impulse "the mystical anarchy of the Hebrews"), you might get a kick out of my crazy little essay, "Waving Farewell to Byzantium" (https://sabbathempire.substack.com/p/essay-10-waving-farewell-to-byzantium) for something in a similar vein to what you've done so beautifully here, but from the Orthodox side of things...