Folk, Faerie, Pagan, Catholic: Part 3

No frogs were harmed in the writing of this newsletter.

First of all, an announcement. My dear, dear friend, the harpist, singer, composer, and clinician Therese Schroeder-Sheker has a new recording out. Rejoice therefore! Blessings of the Road is an extraordinary listening experience and includes traditional Irish and Scottish hymns as well as two chants from the Divine Office and “Nora’s Crown,” a suite Therese composed following the death of her mother. A few of the tracks feature the sublime playing of the late cellist David Darling. The entire album is just lovely.

And now we return to our regularly scheduled programming…

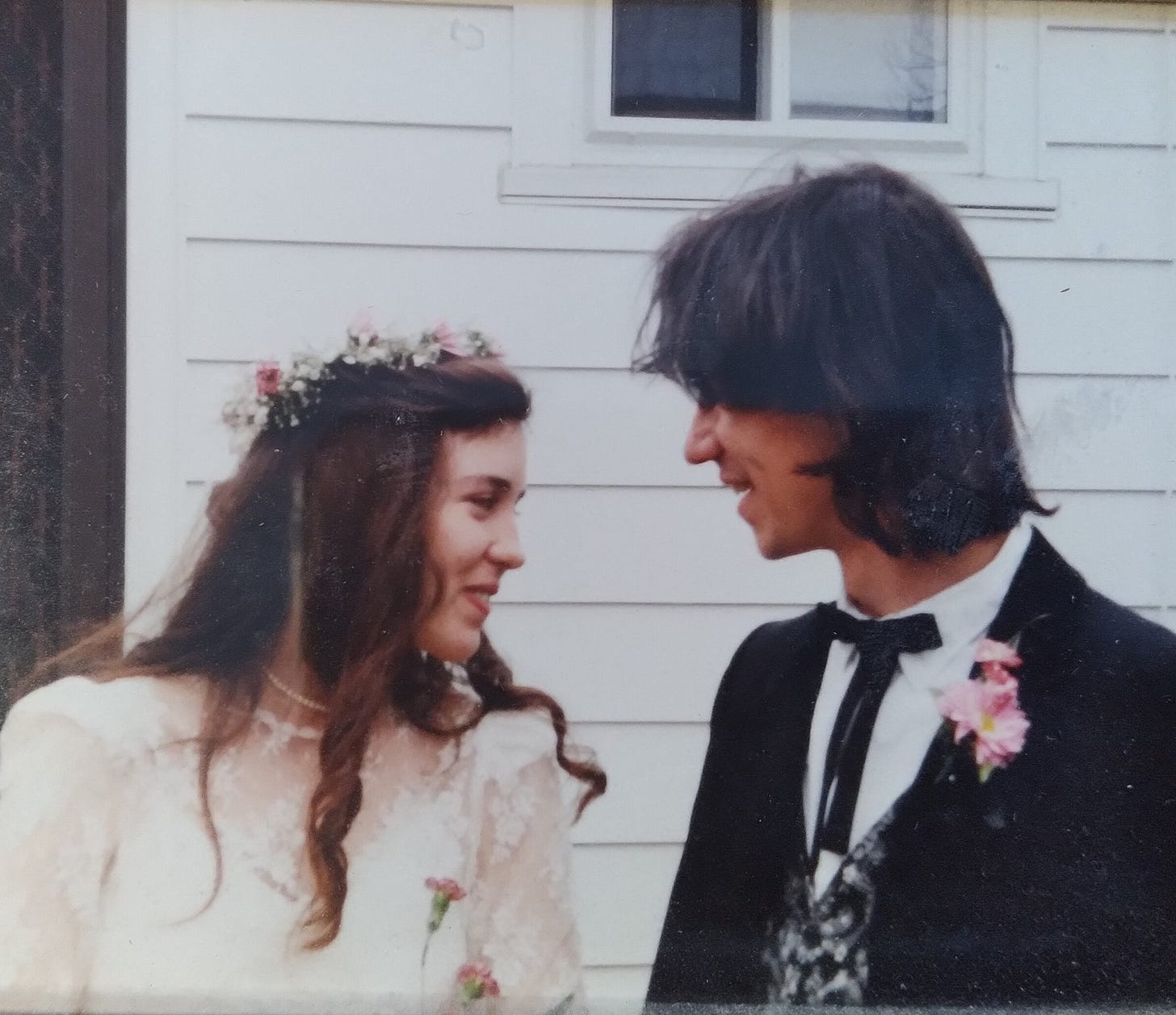

Saturday marked another May Day festival logged in the books of Stella Matutina Farm. I think it was our eighth. We’re those kind of people. In fact, I married the Queen of the May in a garden on a May 2nd thirty-two years ago. And here’s proof:

So we’re weird that way. A few years ago, my then nineteen-year-old son Aidan told me he saw the classic 1973 British folk-horror film The Wicker Man. When I asked him what he thought, he said, “It’s basically our house—but without the human sacrifice.” There’s always next year.

But, kidding aside, it shouldn’t be counter-cultural to celebrate May Day, to grow and raise your own food, to have home-births, lots of children, and to believe that the invisible world penetrates the visible; but apparently it is. And more’s the pity, friends. More’s the pity.

The problem, as I have mentioned many times in The Druid Stares Back, in my old blog, and in my books, is that such an utterly normal and reasonable way of being is so foreign to our modern consciousness and modes of living—which are completely abnormal and anything but rational.

Unfortunately, that abnormality and irrationality also infect the Christian consciousness, mostly because, as Rosemary Haughton writes in her essential text, The Catholic Thing, “evil. . . crept in, and turned the structure of the Church into a bureaucracy more concerned with its own wealth and prestige than with the Kingdom of God. The result was the falling apart of Christendom, and a sickness in the Catholic Church itself which took many centuries to cure.” Rosemary, writing in 1979, is pretty optimistic here. But the sickness in the Catholic Church is now more acute than ever; and there’s no cure in sight. And those who think the same doesn’t apply to their own churches—or religions, for that matter—probably need more oxygen.

For Haughton, as for me, a way to heal this pathology is to renew the obvious connections between the cosmic year and the liturgical year. “Yet perhaps the enterprise was worth while all the same,” she writes,

“For a while, men’s and women’s lives unfolded not only through the natural seasons but in each season were also caught up into the succession of the liturgical year. Medieval popular songs link spring and resurrection, the darkness of winter and the light of the new-born Saviour at Christmas. St. John’s day was midsummer day; pagan and Christian symbols became indistinguishable. Harvet thanksgiving blended with the old fertility rites, and the Mother of Jesus presided over the gathering of the Earth Mother’s plenty. Wild flowers acquired names of saints as well as of the ailment they helped cure—St. John’s Wort, Lady’s Bed-straw, Star of Bethlehem, as well as Lung-wort, Eye-bright and Pile-wort. The bells that called the monks to prayer called the labourers to the fields, and in the fields men bowed their heads, perhaps perfunctorily, at the sacring bell of the Mass, when God was made Bread again, heaven and earth joined inextricably.”

What Haughton describes here are not only liturgical practices, but folk practices intimately tied to, but not identical with, the liturgical practices they accompany. This morning, for example, a friend shared a link to a 1971 BBC program entitled Dusty Bluebells, a short documentary on the children’s songs sung on the streets of Belfast (this was during The Troubles). Now I was a boy in 1971, and even in Detroit (where I grew up) we still maintained the vestiges of the kinds of folk practices in the film that have since disappeared from Western cultural life (with the notable exception of jump-rope rhymes—but I fear even those have almost entirely disappeared). When I was a little boy, for example, it was thought improper for children to knock on the door or ring the doorbell in order to call their friends out to play. Instead, we sang their names from the doorstep. I don’t know when this folk practice vanished, but vanish it did. And not to anyone’s benefit.

One of the things I loved about Sir James Frazer’s The Golden Bough when I read it thirty-some years ago was the variety of folk practices he enumerates. The subtext of ritual or symbolic human sacrifice in Frazer (which clearly influenced David Pinner, who wrote the novel upon which The Wicker Man is based) was not nearly as interesting to me as the practices themselves. On the other hand, as a Christian I have no problem seeing Christ as a vegetation god, actually as the Vegetation God since his death and resurrection made all things new—even the Earth itself. Even legend. This illustration from Frazer speaks volumes:

“In some places of the Pilsen district (Bohemia) on Whit-Monday the King is dressed in bark, ornamented with flowers and ribbons; he wears a crown of gilt paper and rides a horse, which is also decked with flowers. Attended by a judge, an executioner, and other characters, and followed by a train of soldiers, all mounted, he rides to the village square, where a hut or arbour of green boughs has been erected under the May-trees, which are firs, freshly cut, peeled to the top, and dressed with flowers and ribbons. After the dames and maidens of the village have been criticised and a frog beheaded, the cavalcade rides to a place previously determined upon, in a straight, broad street. Here they draw up two lines and the King takes to flight. He is given a short start and rides off at full speed, pursued by the whole troop. If they fail to catch him he remains King for another year, and his companions must pay his score at the ale-house in the evening. But if they overtake and catch him he is scourged with hazel rods or beaten with wooden swords and compelled to dismount. Then the executioner asks, ‘Should I behead this King?’ The answer is given, ‘Behead him’; the executioner brandishes his axe, and with the words, ‘One, two, three, let the King headless be!’ he strikes off the King’s crown. Amid the loud cries of the bystanders the King sinks to the ground; then he is laid on a bier and carried away to the nearest farmhouse.”

Those who went before us were more civilized than we and had more fun. But we have Netflix. Vegetation God help us.

For much of the past thirty years I have been trying to discover what kinds of folk practices might be germane to our own spiritually impoverished times. When we were first married, in the age BC (Before Children), my wife and I used to host what one might call bizarre themed parties. One time, for example, we had an impromptu reading of Dylan Thomas’s Under Milk Wood. Another time, we had this kind of play I wrote (“sketched out” is probably more accurate) where we celebrated the life, death, and resurrection of John Barleycorn (or the Gingerbread Man for the youngins). I don’t recall all of what we did, but there was kind of a Faerie Queen meets Herne the Hunter deal. We also had a large (cookie-tray sized) John Barleycorn/Gingerbread Man for dessert. There was also wine. The rest escapes me. There was also wine.

Frazer has a theory about where all of these folk customs come from, but his project—like many of his time—oversimplifies things in honor of THE GRAND THEORY. Still, I wonder where they do come from and how they catch on. After my experience of writing Mythologies of the Wild of God, I have my own theory—though maybe “intuition” is a better word.

I think these customs and practices arise directly from the land. This is what happened to me in the writing of some of the poems in the book when I started to ask the land around my farm “What stories do you have to tell me?” And the land told me some stories. I think this may have been the case with the story of the king Frazer tells above and of John Barleycorn, but also of Tam Lin and so many others. And I think these stories—especially those of a killed and resurrected king—articulate in a folk idiom the Christian mystery. As does the mysterious ancient poem, “Amergin”:

I AM the wind which breathes upon the sea, I am the wave of the ocean, I am the murmur of the billows, I am the ox of the seven combats, I am the vulture upon the rocks, I am a beam of the sun, I am the fairest of plants, I am a wild boar in valour, I am a salmon in the water, I am a lake in the plain, I am a word of science, I am the point of the lance in battle, I am the God who creates in the head the fire. Who is it who throws light into the meeting on the mountain? Who announces the ages of the moon? Who teaches the place where couches the sun?

The problem, of course, is that most of us are not connected to the land in any meaningful way. And this is probably the most abnormal and irrational thing of all and the root cause of our great alienation from all that is Real, all that is holy, all that is true, and all that is good.

In our house church, we combine elements of liturgical and folk practices. It’s very simple, a Christianity of the wild. It stands between the formal and the informal, between the liturgical and the agricultural, between the natural and the supernatural. I always invite the presences of the invisible ones—the saints and angels, the faeries and elves, Christ and Sophia. “For we know that the whole creation groaneth and travaileth in pain together until now. And not only they, but ourselves also, which have the firstfruits of the Spirit, even we ourselves groan within ourselves, waiting for the adoption, to wit, the redemption of our body” (Romans 8:22-23).

Ah! I remember reading Rosemary Haughton back in those more hopeful days! Just today, I was talking with a friend about the discernment necessary to ordain a priest. I remarked that the best priest was someone who was a priest to all human beings, not just Christian ones. The creeping fundamentalist and literal mindedness, the loss of the deep folk tradition that was part of our ardent belonging, and other unfortunate (and often online) matters are now dividing us so completely. I have spent time on both sides the divide and, like Rosemary, maintain hope to enable the bringing together of all people of faith and good will. I am still glad that we both have kept the doors open, for the hospitable hearth is still the place of magical communion.

Another wonderful essay. I so much agree with everything you say here. The loss of contact with nature - which I suffer from as much as any city dweller even though the green world is only 10 minutes away- is sad. How often do I go? Not often enough. The dislocation of our lives from that of the seasons and the earth is truly horrible, but the amazing thing is - it’s still there. I hope we get to meet up one day. We share so much.