One of the most destiny-altering moments in my life occurred when I was eighteen and my girlfriend and I went to the Detroit Institute of Arts to see an exhibition on the Symbolist Movement. The movement, which arose in late-19th century along the border between France and Belgium, was in some dimensions a reaction against the scientific materialism of the times and the encroaching naturalism of the Impressionists. The Occult Revival and the Celtic Twilight movements of the same era raised their flags for similar reasons. What was life-altering about that visit to the DIA, however, was not informed by such academic or historicist concerns. Rather, my response was simultaneously more visceral and more spiritual. For it was then that the sleeping poet in me was awakened.

Now I had always written poetry and I was then on my way to becoming an accomplished songwriter, but until that visit to the museum, I didn’t have an aesthetic—or even know there was such a thing as an aesthetic. But it took years to realize what had happened to me there.

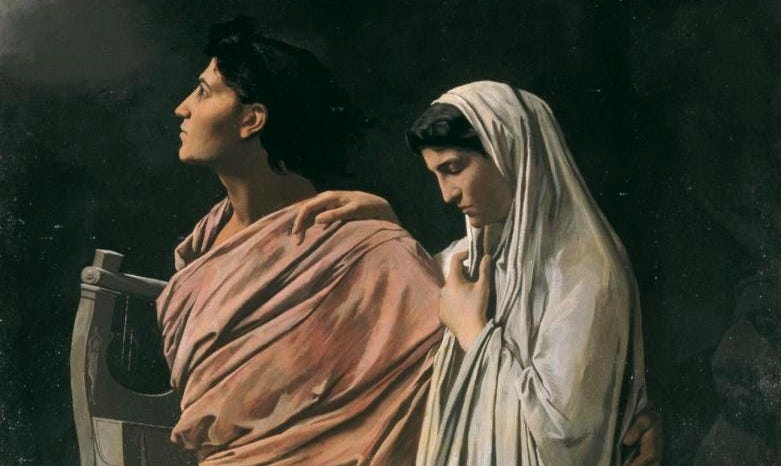

Two subjects that appear again and again in the art and literature of the late-19th/early 20th centuries are John the Baptist and Orpheus, two patron saints decapitated by the insane forces of their times: the Baptist by Herod due to the coercion and manipulation of Herodias and Salome, and Orpheus, literally, at the hands of the Maenads. These two figures were fitting symbols in the rapidly changing European society of the era: an era that had lost its center and was given to, on the one hand, a masculine cold rationality, and on the other, to a feminine unbridled hysteria. That is, times like our own.

One towering figure of the era was the Polish-French poet, Guillaume Apollinaire (1880-1918), one of the most important poets of the 20th century. In his collection The Bestiary (1911—I will be giving the English titles so as to not come off as too pretentious lol ), which is subtitled, “Or the Parade of Orpheus,” he has four poems about both Orpheus (I’m only including three) and one on John the Baptist (here in Pepe Karmel’s translation):

Orpheus Admire the awful strength! The noble lines: His the speaking voice of light As Hermes Trismegistus in his Pimander. Orpheus Let your heart be the bait, the sky your pond! Sinner, what salt water fish or fresh Can match the beauty and the savor Of that divine fish, JESUS, my Savior? Orpheus The she-kingfisher, Love, and winged Sirens Know deadly songs. Don’t heed those wretched birds, But hear the Angels of paradise. The Grasshopper See the fine grasshopper, That nourished Saint John. May my verses be like him, A feast for the best of men.

Apollinaire eventually described his aesthetic as “Orphism,” a kind of poetry or painting equivalent to absolute music: a pure art without any references to influences or conditions. Some of my all-time favorite poems—“Poem Read at the Marriage of Andre Salmon,” “Zone,” and “Phantom of the Clouds”—are gifts from his genius. (If you’re looking for a nice English translation, I highly recommend that by Roger Shattuck and published by New Directions). Although all too long to reproduce here, I can’t resist but share this line of his credo from the Salmon poem: “I know that only those will remake the world who are rooted in poetry.”

Five years Apollinaire’s elder, the Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926) wrote an entire sonnet sequence to Orpheus. The Sonnets to Orpheus is an astounding collection of fifty-five poems written in February of 1922—this while he was completing his likewise astonishing Duino Elegies, in what must be the greatest burst of creative energy in the history of poetry. To give but one example (and it is difficult for me to pick just one), here is sonnet 1.2 in the translation of my dear friend Daniel Polikoff (you can pick up a copy of the entire sequence here):

And it was almost a girl who emerged from the consonant pleasure of song and lyre and shone through her shady spring attire and made her bed within my ear’s drum. And she slept in me. And her sleep was everything. the trees I always marveled at, those palpable distances, the deeply felt meadows and every wonder that touched my human being. She slept the world. Singing god, how did you perfect her so she never sought awakening? See, she rose, and slept fast. Where is her death? O, will you invent it now —this time—before your song burns out? Where is she sinking away?. . . A girl almost. . .

Another contemporary of both Apollinaire and Rilke actually turned Orpheus into a kind of (non-commercial) franchise. He also, unlike them, lived to old age. Jean Cocteau (1889-1963) is a fascinating multi-talented genius, who brought his poetic sensibilities to film. In 1930 or thereabouts, Charles, Vicomte de Noailles, gave Cocteau a million francs to make a film. Cocteau, experienced as an artist and poet, had never made a film, then a fledgling artform. He made Blood of a Poet (1932), certainly one of the most important avant-garde films ever made, if decidedly strange. It would become the first of his Orpheus Trilogy, the other two being Orpheus (1950) and Testament of Orpheus (1960). All three are meditations on the vocation of the poet—which is often a tragic mixture of success and self-sacrifice, the mysterious and the mundane. Ans, as an aside, if you haven’t seen his film, Beauty and the Beast (1946), you’re really missing something.

Blood of a Poet

Orpheus

Testament of Orpheus

All three men lived through the rise of the automobile, the appearance of radio (and film), as well as World War I (in which Apollinaire was badly wounded); and Cocteau lived through World War II and into the turbulent 50s and 60s. They were times of cultural upheaval and madness. These were the kinds of times that would kill prophets and poets in the hysteria of the cult.

Our times, a hundred years later, are not much different. But now almost no one reads poetry, as it is not seen to be worth the trouble. Yet poetry is one form AI will never conquer, as it will never conquer any true art. True art and poetry rely on intuition and imagination—two things AI will never possess—and they rely on the intuition and imagination of not only the poet or artist, but of the reader and beholder as well. The movement of great poetry and great art, then, is not in the material of the media—be it paper and pen, brush and paint, chisel and marble, or what have you. Rather, the movement of poetry and art is in the soul. For that is where you will find Orpheus (and in the early Church, the image of Orpheus—who traveled to the Underworld and also received a horrible death—was a cipher for Christ).

In closing, here is my Orphic poem “Bysios” from Mythologies of the Wild of God. (“Bysios” is the ancient Greek month in which the Pythian priestess delivered her oracles on the birthday of Apollo):

BYSIOS

Dawn: the light over the farm and the fields, the budding oaks brazen and impervious to green

The language of birds: the bark of a crow, a rooster’s arrogant call, the lilting peal of robins, a hammering woodpecker, starlings and their mechanical rasp, redwings whistling in the marsh . . . and I remember the fallen sparrow’s nest under the white pine with strands of my grey hair cushioning the chalice

The intermittent shirr of truck tires over Mount Hope Road

The trilling descant of toads in the flooded woods

The lowing of a newborn calf

The white noise of the moon

A sound from the river, a sound I do not hear but sense.

A summons.

The river: a hollowed oak limb on the bank clouded with bees,

The air sweet with the scent of the queen,

Leopard frogs and salamanders in the shallows.

Trout hover and shine in the shimmering light of the rushing water.

Without removing my boots, I wade into the water, waiting, listening.

The thrumming of the bees, the music of the river,

The rise and fall of the wind in the trees.

A cluster of black alder at the water’s edge . . .

Something snared on the surface by the branches:

The head of the god, a lyre, the holiness of all singing.

Thanks, Michael for this beautiful meditation on a most important topic. What are poets for in needy times ("Wozu Dichter in dürftiger Zeit") asked Hölderlin, but is it not clear that is precisely in the darkest hours that humanity needs the wisdom of those who have descended and can sing of the depths as well as the heights of human experience, and knows (like Rilke) their essential unity? (Thanks for the nod to my translation of the Sonnets, by the way). Your Bysios poem is marvelous: one of my favorites in the collection. I am moved to post here one of the poems from my ekphrastic sequence, this one on the Christic Orpheus and the theme of the (singing?) head:

7. MUSE FINDING THE HEAD OF ORPHEUS

After Edward Berge

This stone is not a Pietâ, and yet

the grace of the Muse as she bends over

the orphaned head (her slender arms sloping

down to cradle it; her gaze declined

in grief) mirrors the gesture the Virgin makes

mourning her lost child. And no wonder

this affinity, this shared communion,

for the Muse is always Mother of creation

and the Son a sort of song—the ebb

and flow of life and death, their rhythmic

alternation. Does the head still sing? The Muse

listens even as she takes it in her arms.

~DJP

Love this, and this line: and I remember the fallen sparrow’s nest under the white pine with strands of my grey hair cushioning the chalice

I have your books on the incarnation of the poetic word in my lists, so what I know is absent that, but poetry is clearly the bow of burning gold to fight AI, which is infiltrating religion and organizations that form communities for people who experience the nonordinary. Some Kissinger loving freak, who has renamed himself Archedon (always a clue) has brought his AI "Glyphon" to the iands community, which was once a place for people who had near death experiences, only now he's had a special unique NDE, (of course he has),which confers authority, kind of like the New Apostolic Reformation "prophets" who would have "visions" that everyone had to obey. And I read that the churches are being attacked by an AI agenda also, all of this now in preparation for the interdimensional chupacabras that the new AI god, a male with breasts, will come riding in on from its Palantir incubation no doubt. Soon there will be speed dating for us with Meta's AI friends or Elon's robots. Iain McGilchrist, in The Master and his Emissary, says "Let's not forget that it was with music that Orpheus once moved stones." And it is in Motherese, baby talk, that the universal poetic line begins, says Ellen Dissanyake in Art and Intimacy(and Frederick Turner) which becomes then the Great Mother, which will be Mary, whose scent of roses remembers the indoles in the mother's body. One of the prompts in a poetry mooc I took before the world went off the cliff was "write the last poem you will ever write" Very clarifying. Thank you for this lovely essay. I've sent it on.