Sophiology, Sex, and Marriage: A User’s Guide

Let my beloved come into his garden, and eat the fruit of his apple trees.

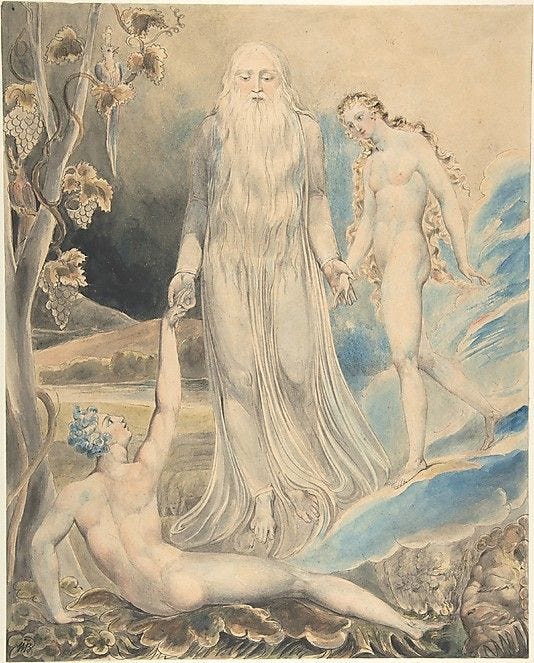

William Blake, “The Angel of the Divine Presence Bringing Eve to Adam” (1803)

Not too long ago I ran across a comment on Twitter in which this traddie-leaning Catholic guy was publicly confessing how compromised he feels spiritually after he has sex with his wife (I usually would have written “made love,” but I don’t think that would be an accurate description in this case). He said this even though he was holding his three-year old on his lap, though I assume he was wearing a hairshirt. I immediately unfollowed him. I just don’t need that kind of negativity in my life.

This came to mind recently when I along with quite a few other individuals (all dudes save one woman) was invited onto Paul Vander Klay’s YouTube channel for a conversation entitled “Why is the Church Today so Sex Positive when the Ancient Church was so Sex Negative?” I think I was invited to represent the “sex positive” side of Christianity. “I’m actually ‘marriage positive,’” I kept repeating. But, yeah. I felt like a visitor from another planet.

In fact, as anyone familiar with my books would know, marriage is one of my primary subjects of interest. It is, indeed, a mystery—and I don’t completely understand it. And that’s a beautiful thing.

I’ve written many love poems in my day, as poetry is my primary vehicle for coming to understand the world. My wife has a trunk at the foot of our bed filled with these love poems and the petals of roses I used to bring her when I worked as a gardener. I wrote this one for her on the birth of one of our children:

MARCH

She didn’t want to wake me, but staccato breaths call me across the threshold. Time for a bath. Time for the kettle to boil. It’s warm for March, so we open the door. Robins sing and wrestle twine from garden stakes.

One March we made love in a pine grove. In the distance, church bells pealed, while above us a family of crows sang like gypsies, invisible in the dark canopy. Though it was cold, we slept on the ground. Pine needles clung to our hair, and all through the day I could smell the pleasant musk of woman.

Tonight I will dream. I will dream I lift a stone and find the heart of a tree. Within, a mouse-colored owl sleeps in a nest of feathers. I will take two feathers before I leave, their quills weighted with flesh.

So I think that line from The Dead Poets Society holds true: “Language was invented for one endeavor...to woo women.” I will die on this hill.

So, on the sophiological behalf of sex and marriage, I thought I might share a few excerpts from my work on the topic, in particular from my edition of The Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz and my most recent book, Sophia in Exile.

The Chymical Wedding

First of all, and perhaps too obviously, the existence of the concept of marriage implies the presence of the erotic. In the early modern period no less than at other times, marriage was understood as a procreative institution concerned, among many other things, with fertility and the raising of children exemplified by Genesis’s injunction “Be fruitful and multiply” (1:28). But this was not simply, despite what some theorists have asserted, a business transaction with birthed children as the currency of a very real human capital. Rather, marriage was understood as a divine ordinance, an ontological structure of the cosmos. In short: it’s how things work. And eros, as Plato was so aware and Christian mysticism has upheld, infuses all that is….

While classical philosophical speculations about eros tended to diminish the importance of gendered typology (without entirely discounting it), the Genesis account of creation attends more phenomenologically, one even could say more scientifically, to the ontological structures of being in this world: “Let us create man in our image, after our likeness….in the divine image he created him; male and female he created them” (1:26, 27). Indeed, István Cselényi, as did Alexis van der Mensbrugghe before him, wonders whether the “us” of Genesis 1:26 implies the feminine Sophia, the Wisdom of God, as God’s partner in such creation—which is certainly a more consistent reading of gendered biblical typology (and supported by Proverbs 8 among other scriptural witnesses). Indeed, Margaret Barker’s recent scholarly excavations of First Temple Judaism suggest that the originary form of Jewish worship included reverence for Wisdom before she was expelled from the Temple and all but expunged from scripture following the reforms of Josiah. In the light of Barker’s discoveries, perhaps the intuitions of Cselényi and Mensbrugghe (as well as my own) are not all that unfounded….

During the Florentine Renaissance, Ficino wrote of Venus as “the power that moves the visible world, infusing the transcendent order into the corporal,” a palimpsest of which persists in The Chymical Wedding. The vision of Venus presages Christian’s achievement of the chymical wedding, even though he receives a wound (from her son Cupid) for his transgression: everyone who touches the mysterion does not come away from the encounter unscathed. But can an eternal goddess in fact die? Can she really be dead? Indeed, is the goddess of love and spirit of marriage not even now entombed? Does she await new Christian Rosenkreutzes to undertake the adventure of restoring her? In Andrea’s time the metaphor of the veiled and hidden goddess was simultaneously scientific and theological. Today it remains both of these things. But it is also political….

Marriage, moreover, as the Book of Revelation and even the Greek mysteries witness, is a telos, but without its elevation to mysticism it inhabits a realm that is neither mysterious nor sacred and becomes a fraud, a sham, a carcass: something in need of regeneration. “Marriage as a sacrament, mystical marriage,” writes Nicolas Berdyaev, “is by its very meaning eternal and dissoluble. This is an absolute truth. But most marriages have no mystical meaning and have nothing to do with eternity. The Christian consciousness must recognize this.” This is a hard saying.

In the alchemical literature, the coniunctio oppositorum (conjunction of opposites) emblematizes an important paradigm of human flourishing: it is only by uniting opposites that the miracle can occur and the work be accomplished. As The Golden Tract has it,

“Know that the secret of the work consists in male and female, i.e., an active and a passive principle. In lead is found the male, in orpiment the female. The male rejoices when the female is brought to it, and the female receives from the male a tinging seed, and is coloured thereby.”

This telos, indeed, reaches beyond the grave and realizes its promise in the glorified body, which the alchemists were so bold as to assay with their materia this side of the Parousia. It is no surprise, then, that the marriages of alchemical practitioners Kenelm Digby and Thomas Vaughan figure so strongly in their own work. Digby, whose wife Venetia predeceased him by over thirty years, considers her glorification with scientific candor: “I can not place the resurrection of our bodies among miracles, but do reckon it the last worke and periode of nature; to the comprehension of which, examples and reason may carry us a great way.” Vaughan’s wife Rebecca (whom he referred to as “Thalia” in much of his writing) served not only as his life partner, but also as his partner in alchemical experimentation; and she continued to inspire him and his work through his dream-life following her untimely death at the age of twenty-seven in 1658. As Donald R. Dickson describes it, for Thomas, even after her death Rebecca served as “tutelary spirit through the medium of his dreams, as spiritual lover who teaches him the sublime mysteries of eternal versus earthly love…and as idealized muse.” The idea of a “chymical wedding” certainly had other than materialistic applications for Digby and Vaughan.

The mystical understanding of marriage, albeit now compromised by legalistic and absolutely un-erotic determinations conditioned by a ghastly parody of the chymical wedding joining neoliberalism, socialism, and capitalism, persists in some quarters of contemporary culture not under obligation to religious or political ideology. In Lindsay Clarke’s novel The Chymical Wedding (inspired by the life and work of Maryann Atwood), for example, the narrator Alex Darken explains the importance of such a gendered typology: “many alchemists had worked with a female assistant—a soror mystica—for the Art required that both aspects of human nature, the male and female, the solar and lunar, be reconciled in harmonious union if the chymical wedding was to be celebrated.” Likewise, in the climax (note the apt metaphor) of Wim Wenders’s film Der Himmel über Berlin (known to English-speaking audiences as Wings of Desire), the trapeze artist Marion instructs her beloved, the newly incarnated in the flesh angel Damiel, regarding the significance of such a union:

“You and I are now time itself. Not only the whole city—the whole world is taking part in our decision. We’re more than just the two of us now. We embody something. We’re sitting in Das Platz des Volkes. And the whole place is full of people with the same dream as ours. We are defining the game for everyone. I’m ready. Now it’s your turn. You hold the game in your hand. It’s now…or never. You need me. You will need me. There is no greater story than ours, that of man and woman. It will be a story of giants... invisible... transposable... a story of new ancestors. Look…my eyes. They are the image of necessity, of the future of everyone in the place. Last night…I dreamed of a stranger... of my man. Only with him could I be alone, open up to him, wholly open, wholly for him… welcome him wholly into me. Surround him with the labyrinth of shared happiness. I know... it’s you.”

Indeed, the union of the mortal Marion and the incarnated angel Damiel, marriage of matter and spirit, is nothing if not an image from the pages of alchemical tracts of the seventeenth century only translated into a postmodern idiom filtered through the language of Rilke. And I have nothing but admiration for Wenders when we hear the applause (ostensibly for Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds) at precisely the moment when Marion and Damiel kiss.

Sophia in Exile

The Song of Songs, such an anomaly in the canon of scripture with its deep and affirmative eros, offers us a glimpse into a sacred sexuality of the marriage chamber that, through most of its history, official Christendom has ignored, forcing allegorical readings upon the plain meaning of a text that even Benedict XVI at last conceded was “intended for a Jewish wedding feast and meant to exult conjugal love.” Nevertheless, the primary interpretive mode when confronting such an erotically charged text has been to read it as an allegory for God’s relationship with the soul (or the Church). The Song of Songs, that is, was co-opted by monasticism and wrested a healthy Christian relationship to sexuality away from the laity, veritably turning the Song into a Lacanian objet petit a, an unattainable object of desire. As Peter Dronke explains, “Theologians, predictably, either ignored the erotic wellspring of such language or recognized it only in order to reject it. Yet inevitably this fons hortorum continued to flow in a poetic hortus conclusus, where mystical and sensual expression and imagery grew together, a garden that was to be of lasting importance for the European imagination.” In fact, the Song was the most-often commented upon text in the medieval cloister, a trajectory that was set in late-antiquity with Origen (how often that name comes up!). Origen offers a confusedly transgendered reading of the Song as an “epithalamium ... which Solomon wrote in the form of a drama and sang under the figure of the Bride, about to wed and burning with heavenly love towards her Bridegroom, who is the Word of God.” No one unfamiliar with the traditional allegorical interpretation of the Song would ever come to such a conclusion. Talk about a violence du texte. It’s not that Origen doesn’t know about the plain sense of the poem. He most certainly does:

“But if any man who lives only after the flesh should approach it [i.e., the Song], to such a one the reading of this scripture will be the occasion of no small hazard and danger. For he, not knowing how to hear love’s language in purity and with chaste ears, will twist the whole manner of his hearing of it away from the inner spiritual man and on to the outward and carnal; and he will be turned away from the spirit to the flesh, and he will fasten carnal desires in himself, and it will seem to be the Divine Scriptures that are thus urging him on to fleshly lust.”

I assume Origen is referring to the same Divine Scriptures that tell the survivors of the Flood to be fruitful and multiply. But I digress….

Some have argued that some religious proscriptions on sexuality in both Judaism and Christianity are not based on a fear of sexuality as a species of spiritual pollution, as one might find in some forms of Gnosticism, but due to the fact that the creative power of God is present in the procreative powers manifest in conjugal union. Because procreation is a property of God, one must be purified after having touched these mysteries—whether they be of sexual congress or of menses. This is, I admit, a useful way to think about it. Unfortunately, that is not how it works out in reality, and often religious rubrics reach absurd conclusions. As noted earlier, Evdokimov observes that “Certain forms of asceticism that prescribe avoiding one’s own mother, and even animals of the female sex, say a great deal about the loss of psychic balance.” Indeed, the practice of not allowing women—and even animals of the female sex—on Mount Athos (clearly alluded to by Evdokimov) is pathology writ large. A friend of mine, to share a tale, once visited Athos. He was happily married and with young children. Nevertheless, monks on Athos tried to get him to abandon his marriage and its sacramental bond and join their fraternity. They assured him they could “work things out” for him. Absolute insanity. Again, from Evdokimov: “It is with the hermits that the ‘woman question’ becomes most current, reducing it to its ‘passionate’ aspect and compromising it forever. Certain theologians deem it useless to propagate the human race; they reduce marriage to the one aim of avoiding incontinence. This is why a conjugal love that is too passionate borders on adultery.” Is it any wonder that there is confusion about sexuality—even within the precincts of marriage—in the Christian psyche? This insanity lies deep in the Christian consciousness, as this statement from a fourteenth-century Encyclopedia of Canon Law makes only too clear in its instructions for married archpriests:

“The divine Fathers of the Sixth Council in their twelfth canon forbid archpriests after ordination to live at all with their legal wives who were joined to them by marriage before ordination; and state ‘we do not decree this for the abolition of what was legislated by the sacred apostles in their fifth canon, but to bring about the Church’s advancement toward that which is better.’.... They say it is necessary for archpriests who govern their lives with strict chastity, not only to abstain from sexual intercourse with other women, but also with their own wives.... Next, they apply the penalty of defrocking to those who do not observe the canon.”

Today, for some reason, married deacons and priests in even the Catholic Church are advised to avoid sexual intercourse the night before participating in the Mass or Divine Liturgy. Jewish tradition, on the other hand, argues that husband and wife uniting in loving embrace on the Sabbath are participating in God’s union with his Shekinah and are thereby simultaneously assisting in the salvation of the world. Which approach sounds the more sane? It should be clear that a serious disruption occurred during the growth of Christianity. The Protestant Reform tried to address this, of course, but the disorder is in the grain….

I suppose that’s enough for now. Let me know what you think in the comments.

A song my wife wrote about the birth of that same child. Recorded by the two of us about 25 years ago.

Join me, Spencer Klavan, Paul Vander Klay, and others in Washington, DC for Christ and Community, and Renewing Culture this July.

In Hinduism, every god has his shakti: his consort, who is his power and life. Vishnu has his Lakshmi, Shiva has his Parvati, Brahma has his Saraswati. From that standpoint, a purely masculine deity would be lonely and strange, almost an abomination. The modern loss of enchantment is almost certainly the result of the neglect of the feminine, since without the feminine, the god has no vital link left with the entire domain of immanence.

Overall, I think that Hinduism—in particular, Shakti theology and Kashmiri Shaivism—is highly consonant with your way of thinking. I would like to go baptize it, with Sophia being the shakti of the Lord. (The deep sense for the syzygy is also why much of Hindu art and sculpture can be so erotic, which more prudish Western sorts might be wont to mistake for vulgar or pornographic.)

I have thought about why Jesus was never married if we posit that marriage is a superior state to celibacy; and I think my answer, in the style of Böhme, is that Jesus must have been the perfect androgyne, carrying his shakti entirely within himself, the way that things probably were before the Great Divide. In that sense, one could suggest that Jesus wasn't so much celibate as he was sort of "pre-married", not having lost the ontological woman within himself.

I have also been playing with the typology of virgin, harlot, bride. To give a positive meaning to virgin that doesn't just denote the absence of the alleged "impurity" of sex, I think it would have to mean a primordial absence of separation. So, I'm thinking that the virgin dwells within God and has never been apart from God. Then the harlot (and I find Hosea to be key here) is the cosmic Woman projected outward and fallen into alienation from God, and the bride is the Woman restored to her communion with God—but from the outside, as it were, and not in the virgin's mode of primordial unity.

Finally, I think that Jung is pretty useful here, since shakti could just as well also be anima, and it seems cogent to suggest that Sophia is the anima of the Lord.

Excellent response Michael. I must admit, I deeply admire Origen and have to wrestle with the urge to defend him. On the other hand I make it a rule to never defend myself when it comes to ideas (unless I’m talking to my husband 😂) so I suppose Origen has things figured out by now. Thanks for challenging the status quo. We need more men and women like you.