“‘Comforte thyselff,’ seyde the kynge, ‘and do as well as thou mayste, for in me ys no truste for to truste in. For I muste into the vale of Avylyon to hele me of my grevous wounde. And if thou here nevermore of me, pray for my soule!’”

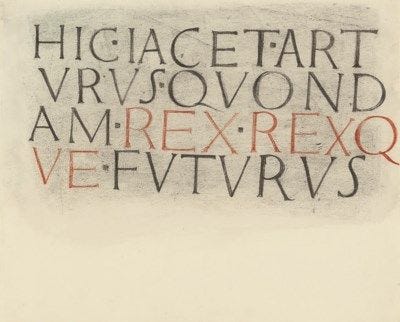

Thus speaks Arthur to Bedivere following the Battle of Camlann toward the end of Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte Darthur (“The Death of Arthur”). It is not a happy ending, but neither is it without hope. Nevertheless, even when the boy Arthur draws the sword in the early pages of the book, an air of melancholy saturates the tale: a melancholy that is never absent, not even for a second. For apocalypse is Malory’s telos; he tells us so in the very title he gives his book. Along the way, from miraculous sword to Camlann, the story circumambulates tales of treachery, adultery, gossip, murder, and betrayal. As Yeats writes in “The Second Coming,” his own apocalypse:

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world, The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere The ceremony of innocence is drowned.

Yeats, writing in the aftermath of World War I, attests to what can be described as “The Myth of the Eternal Return.” The societal collapse he was describing in the early twentieth century is not all that different from the one witnessed by Malory at the end of the fifteenth. Nor is it all that different from that which we are living through now.

Historian Jan Huizinga writes about precisely this kind of cultural and societal decay in his classic text The Waning of the Middle Ages (1934). For him, medieval Christianity essentially exhausted itself, ran out of gas, if you will. I don’t know that his assessment is entirely correct, though it certainly mirrors the landscape and architecture of Morte Darthur.

One of the things Huizinga examines in his book is the decay of the symbolism that had sustained Christianity for the early Middle Ages:

“Symbolism at all times shows a tendency to become mechanical. Once accepted as a principle, it becomes a product, not of poetical enthusiasm only, but a subtle reasoning as well, and as such it grows to be a parasite clinging to thought, causing it to degenerate.”

As a poet, this rings true; and this also may explain why I have found it difficult to “get” what my friend Jonathan Pageau has been doing with his Symbolic World project (though my good friend Nate Hile has tried to explain it to me—lol). It’s also what rubs me the wrong way about the enthusiasm for “traditional verse” among a certain ilk of Christian poet or the excitement over icon writing with some Orthodox (as well as Catholic) artists. It’s all already been said.

In fact, I would point to those efforts to recapture the past (Make Christianity Great Again!) as symptoms of exactly the kind of decline Huizinga describes. I think there’s an analogy with allopathic medicine to be made here. Allopathic medicine, it must be said, really hasn’t done much to prolong life, even though people live longer lives. What it’s done is prolong death. That, in a nutshell, is also the contemporary landscape and architecture of the arts in general and of the Christian arts in particular.

I know this sounds gloomy.

Having said that, as I’ve mentioned previously, I’m getting ready to embark writing an essay on Dylan Thomas as accidental druid, but I’m also starting to get my thoughts around an essay on “The New Middle Ages” as envisioned by Nikolai Berdyaev and Pavel Florensky, among others. Before the waning of the Middle Ages, there were moments of light—among them, gothic architecture, the discovery of the rosary, the learning of the Irish monasteries, and saints Francis and Hildegard—and light certainly illumines the dark, though the dark usually comprehends it not. But I’m a poet, first and foremost, and I know that what makes poetry (and everything else) come to life is (re)discovering the sources of poetic and spiritual truth, not simply recycling old forms in hope that the spirit will somehow take up residence in what was once alive (a real Frankenstein move, when you think about it). Zombie poetry and its zombie symbolism is still dead, no matter how much it moves or how popular it might be. But to return to Malory.

Malory’s book has haunted me for a number of years now. It’s one of those books in which you don’t realize how much it has impacted you until years later. For me, getting older and looking back to see a path of unrealized dreams and regrets certainly is part of that; but so is coming to terms with how this world (and not the world of Sophianic splendor that parallels it) is so utterly in a state of perpetual decay and hope deferred if not destroyed.

In this light, I have a couple of poems based on Malory in my most recent book, Mythologies of the Wild of God, which I hoped to make new in some way. I thought I’d share them. I’m not sure I succeeded in making the material new at all, but you be the judge. As you might be able to tell, I have not always been certain whether I identify more with Arthur or with Lancelot.

AVALON The fragrance of apple blossom and the scent of the lake The waves lulling the shore with their gentle strumming The sun a silver sphere suspended in the midst of dawn Surely, never had there been such a sleeping. And to awaken from the consequences of such sins To such a vision: my sister and my mother restored And my hurts from the battle nowhere to be seen, Only sensed in the ever-bleeding wounds of memory. Though even this, they say, will turn like all things to light. Of the time before so much appears as a dream I have half-forgot, But one thing comes to me with both elation and sorrow: When she, arrayed in ivy and ribbons, rode forth On May Eve, her ladies in attendance, a sparkling escort Of uncommon beauty, delicate as butterflies’ wings And more ephemeral. And though I wanted to call out To tell her to not tarry long in the forest, I failed to speak, My duties of state and import imposing their yoke upon me. And then all things changed: friendship, the kingdom, Sleep—all were lost and left us to the mercy of duration To unravel the good and bring our transgressions to violence. Yet, in my mind’s eye, I see her still, gathering eglantine From the hedges, laughing with her maids in the warmth of the sun, Walking barefoot among the fresh bracken and the violets . . . Only to bear the sorrow of the land upon me once again. VOCATION When first I saw him: beautiful, noble of both mien and of bearing, Standing at sunrise at the lake, the sun behind him and the water Like fire of crimson and gold, the ripples like flame reaching to his feet Wind in his dark hair and his arms full of rushes for bedclothes. We always knew him fearless, but more than that he was kind, humble, Feeling himself somehow unworthy of the accolades, embarrassed even By his contrition, by his weeping when he prayed for the life of young Urry; Even more by our amazement when the lad’s wounds vanished like smoke. So, after a time, seeing him at enmity with his dearest friend we found ourselves All at enmity—with ourselves, with the world—and those who died not from despair In the search for something holy lived in disdain for the abject failure of the Good; And in our anger at this betrayal all was lost in the lust of blood and fire and ruin. The failure of this vocation led him to another, but even then he failed to find solace, Forgiveness cruelly eluding him in this broken cosmos where all that lives can only die. We followed, thinking if we found no comfort at least we would refrain from harm; Yet the barley and corn grew very thin and the heavens were ever masked in grey. One night he was bidden in vision to Almesbury, where he found the beloved already dead. The women wailed and struck up the dirge as he bore the corpse and laid it in the chapel, Offering the Mass of Remembrance while wax candles melted under undulant flame. Even this was a betrayal, for betrayal is as much a property of the world as love. The cloister is also a fellowship, but the dangers here are within and not in the wolds Or on the fields of blood. His loves and friends had vanished, but his vocation yet held Him in thralldom to sorrow. He slept and did not waken, and angels, they say, bore Him away to a lake of rippling waters with waves the colors of crimson and gold.

Well, the Christian ecclesia or assembly hasn’t changed since Paul wrote 1 and 2 Corinthians, he begins by saying of the Corinthian assembly “I always thank God for you because of his grace given you in Christ Jesus. For in him you have been enriched in every way - in all speaking and in all your knowledge - because our testimony about Christ was confirmed in you. Therefore you do not lack any spiritual gift . . . . “ This was all true and other stuff was also true about that assembly and the usual mashup of the good, the bad, the ugly, the true and the false and the beautiful we see living in us and around us was obviously present as we read on in Corinthians. Like when a child matures and can steadily recognize the good and the bad, the weak and the strong in their parents and know that the one doesn’t negate the other, they are both simply true and they love anyway.

“We look forward to a new heaven and a new earth where righteousness is at home” 2 Peter 3:13 In the meantime let us go about doing good as Jesus did. Acts 10:38

"...coming to terms with how this world... is so utterly in a state of perpetual decay and hope deferred if not destroyed."

If, as some people have opined, European Christianity has degenerated into a series of clumsy museums and the EU is a tourist trap for goofy ideas then it, unfortunately, falls to the United States and Russia to rekindle the light. Yet the two champions of faith are carried along by on the one hand the austere visions of Seraphim Rose and the other a nearly exhausted Protestantism, one is hesitant by talk about hope.

Wrapping myself in the warm cloak of our mythical past is a comforting but ephemeral occupation. Yet cherry-picking the ideas contained therein seems to be our only guideposts otherwise we are held hostage to the dubious likes of Mr Musk and his dreams of a glorious Martian civilization amidst the chloride sands and poisonous air. Fitting perhaps for the future of materialism. Or perchance the messianic Jews who call themselves Christians spending their time dribbling over the Old Testament searching for a refutation of the New Covenant.

You are correct to be in a state of melancholy for that is the natural refuge of sanity. Any other stepping stone across the raging river is far more slippery.