Off to the Isthmus, then! To land where wide open the sea roars

Near Parnassus and snow glistens on Delphian rocks;

Off to Olympian regions, up to the heights of Cithaeron,

Up to the pine-trees there, up to the grapes, from which rush

Thebe down there and Ismenos, loud in the country of Cadmus:

Thence has come and back there points to the god who’s to come.

~ Friedrich Hölderlin, “Bread and Wine”

(translated by Michael Hamburger)Do you ever stop to think what a miracle fermentation is? Would there be any culture at all, were it not for horticulture? Are horticulture and its child agriculture not arts for creating beauty and assuring the sustenance of bread risen by yeast and of fermented drink that glads the heart of man, as both the Hebrew scriptures and Greco-Roman myth attest?

I think about these things a lot. I think about them when my wife bakes loaves of sourdough three times a week. I think about them when I place honey, water, and yeast in a fermenting vessel and when I taste the heavenly product of that alchemy. I think about them in every iteration of the Eucharist, the very word which means “thanksgiving.” Why we don’t walk about in a state of constant wonder at and gratitude for these things is one of the great mysteries of existence.

By the time Christianity started to rise to prominence in late-antiquity, the Eleusinian Mysteries had been celebrated for some two-thousand years. The Mysteries were held in honor of the grain goddess Demeter and the recovery of her daughter Persephone (or Kore) from the Underworld. No one exactly knows what initiation into the Mysteries might have looked like, though some, like the Church father Hippolytus, have suggested the central mystery involved showing initiates an ear of gold wheat “in solemn silence.” Others have suggested, instead, that the initiate was granted a “vision” (I assume staged in some way) of Persephone’s recovery and return to the upper-world. I like the second version, but I’m a sophiologist and that’s how we roll. Whatever the case, as Mircea Eliade writes in A History of Religious Ideas, “the Eleusinian Mysteries were bound up with an agricultural mystique, and it is probable that the sacrality of sexual activity, vegetable fertility, and food at least partly shaped the initiatory scenario.”[1] As a biodynamic farmer with nine children, all I can say is “I support this message.”

The Eleusinian Mysteries were, at their core (no pun intended—well, maybe a little intended), the Mysteries of Bread, though I suspect beer was also involved. And why wouldn’t they be? Nevertheless, the Eleusinian Mysteries were rather a “domestic” religious observance—and I mean that in a good way—focused as they were on the mystery of the Mother and Daughter as ciphers for both the agricultural mystery as well as the deeper mystery of being of which they whisper.

The Dionysian Mysteries, on the other hand, don’t appear to have maintained a commensurate level of domesticity. As I’ve written regarding Euripides’s The Bacchae, there was, as we say in the vernacular, some crazy shit goin’ down in the Dionysian Mysteries—which seemed to have included ritual beatings as well as a ritual sacrifice (a symbolic death—don’t get all Girardian on me now). The myth of Dionysus tells of his first birth by a human mother, Semele, and a second birth out of the thigh of his father, the god Zeus—so, he was quite literally, “born again,” a recurring theme in religious initiation that persists even in the Christian Evangelical imagination. But the Dionysian Mysteries are, above all, a very masculine school of mysteries. Inhabiting these mysteries is a theme of the violence necessary to sustain life—the crushing of grapes, with the blood-like juice that oozes from them, and the intoxicating effects of the liquor made from them, are fitting images of precisely this reality. (The English folksong “John Barleycorn Must Die” is a retelling of this myth). I often think of deer hunting as another kind of entrance into the Dionysian Wild: when I hunt the wild and, if successful, take the wild into myself.

Of course, a meditation on the pagan Greek mysteries of bread and wine just begs comparison to the central Christian mystery of the Eucharist. Just as the ceremonial of the mystery religions and the Byzantine court influenced Christian liturgy (and, no, it is not an outgrowth of Jewish cultus), so the sacraments of the Eleusinian and Dionysian Mysteries have a relationship to Christian ritual. I am not saying, however, that the Christian liturgy is a direct case of religious and symbolic larceny from the Mysteries (the Old Testament and Sabbath prayers commemorating the sanctity of bread and wine argue otherwise), but I do think they speak to a similar, multi-valent mystery of being. Only, with Christ, it gets far more personal: “This is my body…. This is my blood.”

Actually, there is an argument to be made that the Gospel of Saint John is fashioned upon a scaffolding based on the Dionysian Mysteries in general and The Bacchae in particular. In fact, the argument has already been made by Mark W. G. Stibbe in his book John as Storyteller: Narrative Criticism and the Fourth Gospel (Cambridge, 1994). The parallels are enticing: turning water into wine at a wedding (talk about fertility!); a god who is rejected by those to whom he appears and wishes to offer salvation; the importance of women among the disciples of each. In Dionysian myth, vines appear miraculously in theophanies of the god. In John’s Gospel, Jesus calls himself both “the bread of life” and “the true vine.” Jesus also tells his listeners “He that eateth my flesh, and drinketh my blood, dwelleth in me, and I in him” (6:56)—and he is not speaking metaphorically. We know this because some turned away, saying “This is a hard saying,” which in modern parlance might be translated as “I can’t get with that, bruh.” It’s also interesting that, though it is the most eucharistic of all the gospels, the Last Supper does not appear in Saint John’s Gospel. Some have argued that this is because John’s Gospel, as it has come down to us, has been somehow damaged along the way. Carl Kerényi has a better explanation:

“When the fourth Evangelist was writing, the Last Supper had already become the great mystery action of Christians. The Evangelist thought the story of its founding and first occurrence too sacred to be narrated in a book intended for the public. In place of it he wrote that Jesus equated himself with the vine. The consequence of this equation was that Jesus spoke of the wine as his blood, and its extension was that he spoke of the bread as his body. By emphasizing that he is the true vine, he dissociates himself from the vineyard, its vines and events, with which he had identified himself too closely. It was necessary to dissociate himself from the ‘false’ vine, the vine that led people astray, because it concealed within itself a false god and a false religion.”[2]

Eliade writes that Dionysus “reveals the mystery, and the sacrality, of the conjunction of life and death.”[3] He likewise describes the theme of The Bacchae as one of “resistance, persecution, and triumph.”[4] These words can be applied to Christ with no alteration.

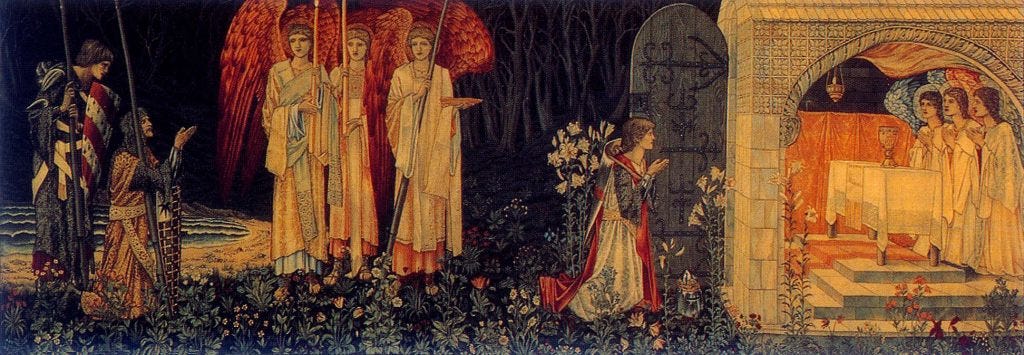

Both Rudolf Steiner and Sergei Bulgakov, one an esoteric philosopher and the other a Russian Orthodox priest, have written that when the blood of Christ united with the earth on Golgotha it not only united Christ with the earth, but imbued the earth with his spiritual power—a phenomenon which continues and shows no sign of stopping. This, in my opinion, indicates the agricultural mystery of today. That is, what was represented in symbolic and mythic form concerning the mysteries of bread and wine—and the attendant mysteries of fertility and sustenance both physical and spiritual—in the Eleusinian and Dionysian Mysteries is now historically, imaginally, materially, and spiritually true. It is not for nothing that both Steiner and Bulgakov connect this agricultural and spiritual mystery to the mystery of the Holy Grail, the chalice used at the Last Supper. Christianity, then, is in every way a Mystery Religion, though most don’t act as if it were.

[1] Mircea Eliade, A History of Religious Ideas, Volume 1: From the Stone Age to the Eleusinian Mysteries (University of Chicago Press, 1978), 300.

[2] Carl Kerényi, Dionysos: Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life (Princeton, 1976), 258. Kerényi’s emphasis.

[3] Eliade, A History of Religion Ideas, Volume 1, 360.

[4] Ibid., 364.

Sometimes it's startling to consider exactly how far away it all has gotten away from the mystery religion, with people getting caught up in history and politics and abstraction and the never-ending quest for a certainty that will never come, because they're just approaching the thing all wrong. (Makes me think of Nietzsche, of all people: "What if truth is more like a woman?") And then when they can't find the phenomenological basis, they neurotically double down on their own specters and start just *saying* things, as if the force of their desperation would be enough to make it true and real. It's a pretty sad sight. And it seems pretty clear that the revival of the poetic core is the only way that the faith will have a future.

The Time is at hand! 🙌🏾