The Imaginal Realm, the Otherworld, and Theurgy

the final part of an essay on the Imagination

Another way to think of it is to say that The Tibetan Book of the Dead offers a finely-tuned topography of an imaginal realm. The same could be said for Blake’s mythos or even Tolkien’s, to mention only two. But an imaginal realm is not simply “an invented world,” a work of fiction; and both Blake and Tolkien believed the worlds of their works to be as real as any other. On the other hand, every world, including that we take to be “reality,” is a product of invention. The question is: Who is doing the inventing? It is not a welcome realization, is it? As Rilke so wisely observes, “already the knowing animals are aware / that we are not really at home in / our interpreted world.”[1] My claim: the imaginal world is just as substantial as any world, including those we think we inhabit. Another name for the imaginal realm, or at least an aspect of it, is the Otherworld.

The great French scholar and philosopher of religion Henri Corbin explains the characteristics of the imaginal realm:

“Between the universe that can be apprehended by pure intellectual perception and the universe perceptible to the senses, there is an intermediate world, the world of idea-images, of archetypal figures, or subtle substances, of ‘immaterial’ matter. This world is as real and objective, as consistent and subsistent as the intelligible and sensibly worlds; it is an intermediate universe ‘where the spiritual takes body and the body becomes spiritual,’ a world consisting of real matter and real extension, though by comparison to sensible, corruptible matter these are subtle and immaterial. The organ of the universe is the active imagination; it is the place of theophanic visions, the scene on which visionary events and symbolic histories appear in their true reality.”[2]

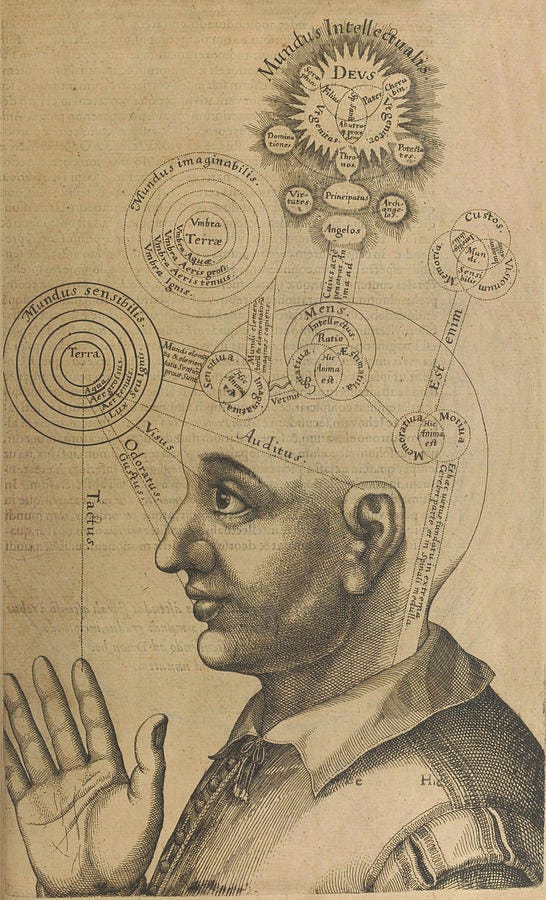

As we have seen, in the seventeenth century Robert Fludd scientifically diagrammed this same realm and its relationship to human perception. For Fludd, it is precisely in such a between realm that the soul appears: Hic anima est.

Though I don’t think they are identical, the imaginal world in which visionary events and symbolic histories appear in their true reality is analogous to the metaxu in which Sophia appears as (and at) the threshold between the Creation and Divinity. Both represent an absolute reality of the structures of the cosmos and of consciousness, though both are almost entirely ignored by contemporary science, philosophy, and theology. Only at the fringes of theology does Sophia find welcome, and only in rare subcultures of the arts does serious consideration of the imaginal obtain purchase.

When confronted with the possibility of an imaginal world or an Otherworld, whether encountered accidentally, via meditative practices, or through the agency of psychedelics, people often raise the question of danger. And, it must be admitted, there are very real dangers to be found in the imaginal worlds—just as in the world familiar to us, not all of the beings in the Otherworld are benevolent. There, as here, some are kind, some are morally mixed, some are mischievous, while others are absolutely malevolent. Fairy-tales, which I am more and more inclined to read as imaginal history rather than “fancy,” are rife with stories of both benevolent and malevolent beings inhabiting the Otherworld, from the fairy godmother to the witch, from the dwarves who provide Snow White with shelter to the plethora of man-eating giants. The world we take as real is likewise full of known and unknown dangers; and a big part of surviving in this world is in knowing where the dangers lie. Those who don’t know the lay of the land in this world may find themselves unexpectedly eaten by wolves, robbed of their money, or sex-trafficked, among many other dangers. The only difference between this world and the Otherworld or the imaginal realm is that not a lot of people have experience (or enough experience) in the Otherworld to know where the dangers are and where the delights. I imagine, as in the Mabinogion, commerce between these worlds was common once upon a time, but over the eons the frontier between these worlds has been demarcated by the theological equivalent of a “There be monsters” warning. Look no further.

As in our perceived world, often in the imaginal world the good guys and the bad guys are not always easily distinguished, often by design. R. Ogilvie Crombie (known as “Roc”), for example, one of the founders of Findhorn, had discussions with a being who identified himself as Pan, the god of the woodlands known to Greek and Roman myth. Pan lamented the ways in which his image had been besmirched by confusion with a being he called “Anti-Pan.” As Pan tells it,

“Everything about [Anti-Pan] is odd. You might regard him as a debased aspect of myself, a detached shadow. We’re quite good friends in a way as he has a necessary part to play. I keep him at arm’s length. . . . His horns are longer and vicious looking. He smells of goat. He is a real nymph-chasing satyr, the goat-god, the true model for the devil. He is very earthy. Unfortunately too many people take him for me; that is the reason for the bad reputation I have in some quarters.”[3]

When Roc asked if it was easy to contact Anti-Pan, Pan replied, “Too easy. Invoke him with the right noises and he’ll be there, masquerading as me.” Roc wanted to know if Pan could do anything about it, and was given a surprising answer: “More than you think but I usually leave it, unless he goes too far. The fools who invoke him deserve what’s coming to them.”

Commerce between the world we think we see and the Otherworld is often dangerous, even to those who don’t deserve what’s coming to them. Such was the case of the Reverend Robert Kirk, the seventeenth century Scottish minister who wrote what amounts to probably the first anthropological study of the Otherworld, The Secret Commonwealth of Elves, Fauns and Fairies. According the Reverend Doctor Grahame, his successor as pastor of the church at Aberfoyle, one evening as Kirk was walking near a dun-shi (a fairy hill) in his village, he fell into a swoon and was thought to have died. After the funeral, according to Sir Walter Scott, Kirk appeared to a cousin and commanded him to go to Grahame of Duchray: “Say to Duchray, who is my cousin as well as your won, that I am not dead, but a captive in Fairyland, and only one chance remains for my liberation. When the posthumous child, of which my wife had been delivered since my disappearance, shall be brought to baptism, I will appear in the room, when, if Duchray shall throw over my head the knife or dirk which he holds in his hand, I may be restored to society; but if this is neglected, I am lost forever.” Kirk did indeed appear, but Duchray, awestruck and flustered by the manifestation (and who wouldn’t be?), did not throw his dirk in time.[4] As R. B. Cunningham Graham writes in his 1933 introduction to the same book, “the natives of the district are well assured that he was reft away, and still lives in the recesses of the Fairy Hill, serving the fairy mass.”[5] Many such stories exist.

Of course, the doors between worlds don’t open in only one way, as we find in the story of the “Green Children,” a brother and sister—actually green of complexion—who miraculously appeared in St. Mary’s of the Wolf-pits (Wool-pit) in Suffolk, England, sometime in the twelfth century. They spoke a strange language and, at first, would only eat broad beans. The boy died not long after their arrival, but the girl lived for many years and even married. After becoming accustomed to the food of her new country, she eventually lost her green complexion and was known for the peculiarity of being “rather loose and wanton in her conduct.” After she had learned English, the girl related that, lured by the sound of bells, she and her brother had wandered into a cave and then emerged in Suffolk, “struck senseless by the excessive light of the sun, and the unusual temperature of the air.” In their own land, she said, “they saw no sun, but enjoyed a degree of light like what is after sunset.” In the account of William of Newbridge, it is related that the children said their country was called St. Martin’s Land, “as that saint was chiefly worshipped there; that the people were Christians, and had churches; that the sun did not rise there, but that there was a bright country which could be seen from theirs, being divided by a very broad river.”[6]

The curious thing about the stories of Reverend Kirk and the Green Children is that they suggest that there are circumstances in which the imaginal stops being imaginal and denizens of either the Otherworld or our assumed world can find themselves trapped as aliens in a foreign world, “belonging to no world of making, lodgers at the threshold of night.” While probably not common, such cases may be more of a reality than we can dream.

As I mentioned earlier, the Imagination is an organ of perception, one nearly atrophied in humankind due to lack of development. Because of this, not only do we lack knowledge of the imaginal or the Otherworld, but, because our imaginations are so weakened, we are therefore susceptible to having our own imaginations manipulated; and the manipulation of the imagination is nothing other than magic: for the manipulation of the imagination all too often leads to the manipulation of the emotions, then of the thinking, and, ultimately, of the will.

Our current social environment here in the West, I would argue, is saturated with magical actions of dark purpose. Propaganda, most of the popular music bombarding us constantly, popular films and documentaries, every sort of news media, as well as political speech the world over are all (or almost all) directed toward a project of mass control, and have literally put untold millions of subjects, if not more, into a spell. And as anyone knows from fairy-tales, spells are not easily broken. The question such a situation poses is only all too obvious: how does one break such a spell?

The impressive magical project of what Edward Bernays (approvingly) called “the invisible government” is all the more impressive due to its organization, planning, and implementation. If it weren’t so evil, it would be commendable. And since magic works on the imagination via image, word, and repetition of the images and words, we find ourselves awash in a sea of incantations that are nearly impossible to resist. Nevertheless, many do resist. But the best way to fight dark movements on the Imagination, is with an Imagination of light.

On an individual level, a sound way to develop the Imagination is through the cultivation of the arts, or of craft, anything from writing poetry or music, to woodworking, to gardening, to blacksmithing. While not failsafe (many people involved in such works nevertheless can find themselves spellbound), these activities do lead one into a contemplative state of beholding, akin to prayer, which certainly strengthens the Imagination. When this happens, the arts can become theurgy. As Nikolai Berdyaev writes,

“Art is religious in the depths of the very artistic creative act. Within its own limits, the artist’s creation is theurgic action. Theurgy is free creation, liberated from norms of this world which might be imposed upon it. But in the depths of theurgic action there is revealed the religious-ontological, the religious meaning of being. Theurgy cannot be either an imposed norm or a low for art. Theurgy is the final bourne of the artist’s inward desire, its action in the world. The man who confuses theurgy with religious tendencies in art does not know what theurgy is. Theurgy is the final liberty of art, the inwardly-attained limit of the artist’s creativeness. Theurgy is an action superior to magic, for it is action together with God; it is the continuation of creation with God. The theurge, working together with God, creates the cosmos; creates beauty as being. Theurgy is a challenge to religious creativity. In theurgy Christian transcendence is transformed into immanence and by means of theurgy perfection is attained.”[7]

Though our world is saturated by things posing as music or film, poetry or painting, sculpture or craft, the theurgic power of these arts is rarely encountered in contemporary settings. In addition, one could argue that the arts as currently practiced have reached their nadir and the aggregated kipple that is AI art, writing, or film proves the ultimate black magic in that its only power is in finally destroying the Imagination. That is to say that AI is the anti-Imagination and completes the atrophy inflicted over the ages on the individual imagination. Once humanity becomes acclimated to AI art, we will become beings without souls.

As Berdyaev notes, “It is not art alone, which leads to theurgy, but art is one of the principal ways to it.” And it is this because it a strengthening and implementation of the Imagination.

I have often wondered where the white magicians are to counteract the vast program of black magic having been perpetrated on humankind for who knows how many generations, but certainly nowhere as evident as over the last few decades. And, understand, I am not talking about ceremonial magicians practicing fumigations, inscribing magic circles, and invoking demons, but technocrats and bad actors behind the projection screen of what passes for “reality.” One has to ask: Is a mass resistance of the Imagination in the face a full-frontal assault on the same even possible?

Of course, liturgical practices, such as those found in the traditional Roman Catholic Mass and the Byzantine Liturgy are great repositories of theurgy, what Valentin Tomberg calls “sacred magic,” and those liturgies, with their chanting, hymns, prayers, artworks, incense, vestments, and the Eucharist itself provide the Imagination with a rich environment in which to flourish (not to mention grace). Nevertheless, the governance structures Catholicism, Orthodoxy, and all varieties of Protestantism have to one degree or another been co-opted by the magic of the technocrats, either voluntarily or unconsciously; and while the sacred magic of the liturgies is still intact, the edifices of these great institutions have lost much in the way of legitimacy. I don’t see them standing up to the technocratic magicians with anything close to an equal level of force. At worst, they are co-conspirators; at best, they are waiting for Jesus to do something about it. I don’t think that a helpful strategy.

If we were to appropriate the tools of the technocratic magicians, we could flood culture with images and languages of the good—in all of the fine and practical arts, in public liturgical celebration, in festival, and even in mourning. To be sure, all these have been tried and all are realities in the here and now—but, since the internet and social media are the prime vehicles to reach a wide audience, the technocratic magicians limit the reach of the Good, the True, and the Beautiful through the clever deployment of algorithms if not outright censorship. But even were those hindrances not in place, the Good would be degraded in kipple simply by the medium itself. There will be no baptizing of the internet or social media. How could there be? Neither one has a substantial reality. Indeed, they represent a synthetic Otherworld, an electronic liminal realm. These are our Satanic Mills.

Blake, though given to dramatic intensity, is the most subtle of poets and the most practical of theurgists. When he writes “And was Jerusalem builded here, / Among these dark Satanic Mills?” he doesn’t answer “yes” or “no.” He answers with a solution:

Bring me my Bow of burning gold: Bring me my arrows of desire: Bring me my Spear: O clouds unfold! Bring me my Chariot of fire! I will not cease from Mental Fight, Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand: Till we have built Jerusalem, In Englands green & pleasant Land.

What Blake upholds here is what Berdyaev calls “active eschatology” which is “the justification of the creative power of man.”[8] That is, it is now time to act, not be acted upon and not wait for the eschaton to come to us. Instead, we need to immanentize not the eschaton but the Imagination (which amounts to the same thing). This terrifies the technocratic magicians, which is why they expend so much energy on keeping us entranced by the spells of their propaganda and the superstructure of their false reality. Take up your weapons, whatever weapons you have been given through the gift of the Imagination, and build Jerusalem.

[1] From the first Duino Elegy, in The Selected Poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke, ed. and trans. by Stephen Mitchell (New York: Random House, 1982).

[2] Henri Corbin, Alone with the Alone, trans. Ralph Manheim (Princeton: Bollingen, 1997), 4.

[3] R. Ogilvie Crombie, Encounters with Nature Spirits (Rochester, VT: Findhorn Press, 2018), 88.

[4] Quoted in Andrew Lang, “The History of the Book and Author,” introduction to The Secret Commonwealth of Elves, Fauns and Fairies by Robert Kirk (Mineola, NY: Dover, 2008), 14-15.

[5] Ibid., “To the Good People,” 11.

[6] Thomas Keightly, The Fairy Mythology (London: G. Bell, 1878), 282-83.

[7] Nicolas Berdyaev, The Meaning of the Creative Act, trans. Donald Lowrie (New York: Collier Books, 1962), 230.

[8] Nikolai Berdyaev, Slavery and Freedom, trans. R. M. French (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1944), 265.

"There will be no baptizing of the internet or social media. How could there be?"

As the daily massgoer Marshall McLuhan said, "The medium is the message"—an extraordinarily powerful insight. (I'm pretty sure that at one level, what he had in mind was that God becoming incarnate in the medium of a human was itself the Message.) Anyway, I found myself scrolling through a Substack comment forum the other day, and it occurred to me that as far as the brain is concerned, digital scrolling is still digital scrolling—even if the content in question is fairly literate and intelligent. It degrades the attention, makes it harder to sit still and focus and read a book.

Nevertheless, there's a doubled-edged irony, I think. The Internet and social media may be intrinsically problematic; and yet it's good to read your essay on this social media platform, as well as to take your online classes. So it seems like there is *some* positive good in there somewhere, having to do with actual human communion, if it could be extracted from the rest of the trash. But I'm not sure.

Jose Arguelles called this matrix inside the illusion the Dreamspell.

Says our natural timeline was hijacked and we have to get it back.

It's coming...