So I bought a book. Actually, I bought several thousand books over my lifetime (I have no idea what number my library stands at currently, other than to say “it’s really a lot!”). But I mean I bought a book this week. And this purchase has plunged me into an ongoing reverie about the objects that surround us and their relationship to the soul.

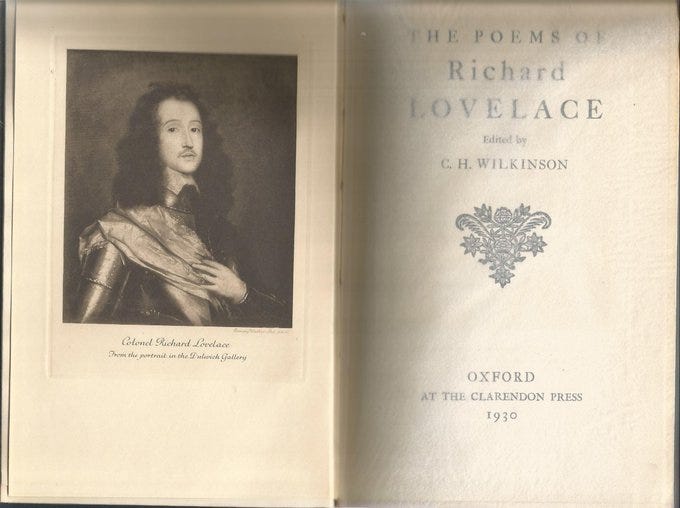

The book in question is The Poems of Richard Lovelace, edited by C. H. Wilkinson and published by The Clarendon Press at Oxford University in 1930. Lovelace, if you didn’t know, was a colonel in the Royalist army during the English Civil War and is for this reason listed among the Cavalier Poets. Though many might not know his name, many will nevertheless be familiar with these lines from “To Althea, from Prison”: “Stone walls do not a prison make, / Nor iron bars a cage.” Lovelace was imprisoned several times for his support of the King. The Puritans were such party-poopers. They also hated dancing and outlawed Christmas. Philistines.

But I don’t want to discuss Lovelace so much as I am interested in this book. And I don’t mean a book of Lovelace’s poetry. And I don’t mean a digital version of this 1930 edition. I mean this book, the one in my hands.

The first thing one would notice on picking up this volume is the weight. It is much heavier than books of its size published since, say, the 1940s. It’s also beautiful. The cover is engraved with gold-leaf and the frontispiece is a copperplate engraving of Lovelace—you can even see the indentation on the page where the copper plate was impressed all of ninety-five years ago. A fine onion skin leaf separates the frontispiece from the title page. And while not a facsimile edition, the graphics of the book are in the style of seventeenth century book publication—and you can actually feel the letters when you run your fingers over the page. It is a beautifully made book.

As you no doubt know, I am deeply involved in the world of book publishing, both as an author and an editor, so I know the trade pretty well. Nevertheless, a sorrow invades my soul that my books and the books I have edited and have loved, including several of David Bentley Hart’s books, cannot hold a candle to the craft of this book—and so many like it—from long ago. Not that all books were made like this—plenty of cheaply made books were published in 1930 that long ago returned to dust—but this Oxford edition represented a standard. And while a quality edition, it doesn’t have a leather binding; that is, it wasn’t “top of the line.” But it was made with care and craftsmanship. I almost feel sorry for the other books in my library in their innate plainness of the perfunctory. What’s worse, I don’t even know if publishers could make books like this if they wanted to, not only due to cost, but because I’m not sure anyone has the skills to make such a book anymore, let alone mass-produce one.

This book sent me into a reverie about the things that surround us in our lives, everything from our dwellings, the furniture and fixtures of our homes, our clothing, etc. Considering what lifeless junk inhabits our lives, I’m almost surprised anyone at all has a soul anymore.

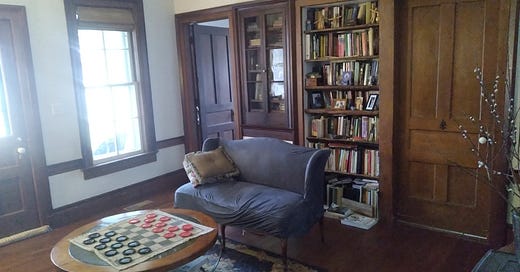

I’m lucky enough to live in a house that is about 160 years old, which is pretty old by Michigan standards, though I suspect in parts of Europe some might think our house is just getting broken in. Our house is an amazing pastiche of old quality and new junk (it’s unavoidable). The doors and woodwork in the house are mostly of black walnut, probably felled here at the farm and milled at a sawmill that used to be about a mile away on a stream of the Grand River watershed. A good number of the doorknobs and hinges have intricate designs (who sees a hinge?!). The floors are mostly of cedar or tamarack, all felled from trees on this land we inhabit. The walls are almost all plaster (there are a few instances of late-arrival drywall—so cheap!). When my wife and I recently met with an insurance agent about homeowners’ insurance and he asked what it would cost to rebuild our house, we all laughed. There is no way the woodwork could be replaced—and the insurance company would only pay for the crap timber that cracks and warps as soon as it’s set in place. O tempora! O mores!

The man who built my house in the 1860s, Charles Moeckel, was certainly a successful farmer (he and his wife, btw, like me and mine, had nine children), but he was no tycoon. Nevertheless, he constructed a house of warmth, style, and comfort: a dwelling for the soul. I think the love for old farmhouses and their singular architecture that people have almost instinctively is due to both an immediate sense of soul when walking into these spaces and the often-unacknowledged realization that the spaces most of us inhabit are not only soulless, but damaging to the soul.

But this is nothing new. Over a hundred years ago, Rudolf Steiner warned about the deadening mass-produced spaces of modernity and his experiments in architecture were an attempt to provide people with an architecture for the soul. One thing he said was in regard to something as simple as a door. For Steiner, when looking at a door, one should, by the door’s shape, intuitively know which way the door should open. A rectangular door offers no such opportunity for intuition. The rectangle is a symbol of utilitarian tyranny. As sensible as Steiner’s insights are, they haven’t exactly caught on.

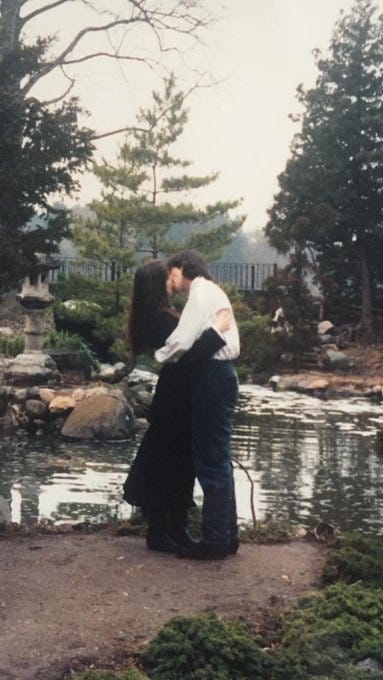

Even before Steiner, John Ruskin and William Morris sought to resist the onslaught of the soulless in defense of the service of humanity. Morris’s extraordinarily beautiful wallpapers and fabrics produced by his company, Morris and Co, “The Firm,” may have since then become the province of the well-to-do, but he intended them for every class. When we still lived in the Detroit area, my wife and I would often go for walks on the grounds of the Cranbrook Educational Community, a community founded by philanthropist and publishing mogul (how’s that for a tie-in to my intro!), George Booth who was a devotee of the Arts and Crafts Movement of which Ruskin and Morris were such pioneers. My wife and I even walked there after we were married on April 11, 1992 (the photo below was taken in the Japanese garden). Indeed, the Cranbrook Art Museum is essentially a temple to William Morris. Christ Church Cranbrook, part of this complex, is, to my mind, one of the most beautiful churches in North America.

In William Morris: A Biography, Jack Lindsay beautifully encapsulates Morris’s aesthetic. Morris, he writes,

“looked outwards for ways in which he could link his craft-activity with the struggle for a better world—a world in which the Ruskinian vision could be realised as a part of a general way of life. He began with the effort to organise resistance to the desecration of the human heritage embodied in old buildings, and to fight for peace against the war forces which he increasingly saw as linked with the forms of human degradation and exploitation at home.”

Let me unpack this a little: dead, soulless spaces, lead to deadened, soulless people, leads to a dead, soulless culture, leads to slavery (even though it might look like freedom) and war. YOU ARE HERE. As Lindsay adds, “For Morris the adventure of freedom is also always a realisation of beauty and a communion with the earth; and so the liberation of the human essence is aesthetic as well as social.”

But we don’t have that, at least not as a norm. Instead, we have what Philip K. Dick (a prophet if ever there was one) in his novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (the book upon which the film Blade Runner is based) describes as “kipple.” One of the novel’s characters is John Isidore, a “chickenhead”—a person who became mentally deficient due to toxic contaminants in the air which settle as dust (I’m sure that could never happen). He may be a chickenhead, but he is almost the only decent human being in the book. Isidore explains kipple:

“Kipple is useless objects, like junk mail or match folders after you use the last match or gum wrappers or yesterday’s homeopape [newspaper]. When nobody’s around, kipple reproduces itself. For instance, if you go to bed leaving any kipple around your apartment, when you wake up the next morning there’s twice as much of it. It always gets more and more.”

I believe we’ve all had similar experiences.

Isidore is ultimately resolved that kipple will win in the end:

“No one can win against kipple…except temporarily and maybe in one spot, like in my apartment I’ve created a stasis between kipple and non-kipple, for the time being. But eventually I’ll die or go away, and then the kipple will again take over. It’s a universal principle operating throughout the universe; the entire universe is moving toward a final state of total, absolute kippleization.”

So what side are you on? Are we headed for the entropy of absolute kippleization—or can the aesthetic arise to rescue us from the deadening of the soul?

In the spirit of Albert Camus, it seems to me that whether absolute kippleization is inevitable is an irrelevant question, because the moral demand upon us is the same one way or the other. Whether it will win in the end or not, we must resist, and we can't surrender; the meaning is in the revolt itself.

Have you heard of Christopher Alexander? He's an architect who developed a theory of resonance between humans and the built environment, and he found that there is indeed an emprical metric—valid and reliable and quite consistent across people—that reflects what we would call the sacred or soulful quality of any given place. It isn't subjective; we're surely sensing an actual thing that is either there or not.

Also, I hope your class on *Jersualem* is going well. Do you know yet what your next one will be on? I'll probably want to join in again.

Made me think of all the convention centers that are called churches that have been to. This overflows into the spiritually of those that worship in those places. Shame on you Christians for making the world into a soulless place.