William Butler Yeats and the Problems of Prophecy

an inquiry

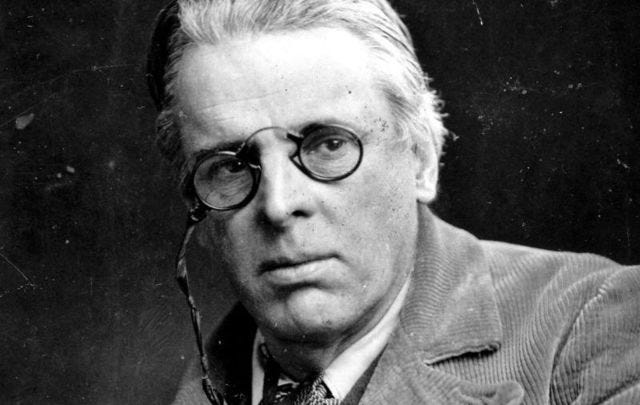

Poet, magician, sometime politician, throughout his life William Butler Yeats was interested in prophecy. Spending summers in Sligo in rural Ireland as a boy, he was nurtured on faerie lore and tales of the second sight told him by the peasant Irish women attached to his household, which no doubt fired his imagination about things hidden. This fascination with the mysteries of the world is no doubt common in children, but usually fades with the years as they grow and become more and more enmeshed in a world more full of weeping than they can understand. But while no stranger to sorrow, Yeats never lost his awareness that there is another world not immediately available to the senses.

This interest in the Otherworld no doubt drew Yeats to many aspects of the Occult Revival then in vogue. While a very young man, he befriended Helena Blavatsky, for example, and his investiture in the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn is well documented. Early in his career, he was one of the first to undertake an exhaustive study of William Blake’s prophetic works. Yeats found in Blake a kindred soul who also understood Imagination as a human capacity for not only the creation of poetic works and art but also for investigation into the spiritual secrets of the universe and seeing into the future.

Common to activity in occult groups like the Theosophical Society and the Golden Dawn is a desire among its members to renew society. This attitude is present, for example, in the Rosicrucian manifestos of the early seventeenth century (Fama Fraternitatis, Confessio Fraternitatis, and The Chymical Wedding of Christian Rosenkreutz) and it is also a feature of Romanticism (and not only in Blake) and in the work of Rudolf Steiner (to name only a few examples). Society, of course, could always use a little renewal.

The desire to build a better world, I would suggest, is encoded in the DNA of our species. Indeed, almost every movement, occult or not, that has appeared over the course of human history—religions and political movements foremost among them—has promised a better world, if only more people would adopt its principles and beliefs. Some have success and some don’t, while others capitalize on the idealistic DNA of the human race in order to exploit it. We all want something to be true and good and will convince ourselves that we have found it even when we haven’t. We are born with, that is, a remarkable capacity for self-delusion, which functions at high capacity in groups of likeminded (or like-deluded) individuals.

Nevertheless, many of us (I won’t say “all,” as tempted as I am to do so) live with what I would call an intuition that some glorious moment lies just beyond the horizon; because, let’s face it, what we have does not offer much in the way of promise. And this is true for atheists as well as those of us who believe in the world of the spirit. Delusion and disappointment are the leitmotif of the human story. But if we didn’t have that intuition of something glorious just beyond the horizon, could we even go on? What’s the alternative?

In 1895, when he was still a relatively young man (he was about thirty), Yeats wrote in a prophetic mood, tinged with the optimism of our race. In a short essay (really just a long paragraph) entitled “The Body of the Father Christian Rosencrux” (clearly a product of his early enthusiasm for the Golden Dawn) he writes in an idealistic register:

“I cannot get it out of my mind that this age of criticism is about to pass, and an age of imagination, of emotion, of moods, of revelation, about to come in its place; for certainly belief in a supersensual world is at hand again; and when the notion that we are ‘phantoms of the earth and water’ has gone down the wind, we will trust our own being and all it desires to invent; and when the external world is no more the standard of reality, we will learn again that the great Passions are angels of God, and that to embody them ‘uncurbed in their eternal glory,’ even in their labour for the ending of man’s peace and prosperity, is more than to comment, however wisely, upon the tendencies of our time, or to express the socialistic, or humanitarian, or other forces of our time, or even ‘to sum up’ our time, as the phrase is; for Art is a revelation, and not a criticism, and the life of the artist is in the old saying, ‘The wind bloweth where it listeth, and thou hearest the sound thereof, but canst not tell whence it cometh and whither it goeth; so is every one that is born of the spirit.’”[1]

Did that age of imagination, moods, and revelation come to pass? Is the external world still the standard of reality? What answer would you give to these questions?

I have my doubts that Yeats’s idealism survived intact into the twentieth century as he witnessed the horrors of World War I and the Irish Civil War among other more personal tragedies (he died 1939, after the rise of Hitler but eight months before the inauguration of World War II). Nevertheless, he did not lose his belief in the supersensual world, nor did he lose his penchant for prophecy; but it was no longer what it had been during the heady rush of youth.

After having failed to properly woo the Irish actress Maude Gonne—and then her daughter Iseult!—to marry him (long story), Yeats at last settled down to marriage with Georgie Hyde-Lees in October 1917, when Yeats was fifty-two and his wife just twenty-five. Four days into their marriage, the newlyweds engaged in an experiment in automatic writing (with Georgie in the role of medium). The experiment proved a great success. Yeats, thinking that the messages they received might have some greater social import, was told, “No… we have come to give you metaphors for poetry.” For the poet Yeats, this was reason enough to continue.

Yeats recorded the fruits of their spiritual researches in his book A Vision, privately published in 1925 with an expanded public edition appearing in 1938. More importantly, the symbols and images received in their communications (gyres, the phases of the moon, the passionate body, the celestial body, and the husk, among others) permeates his poetry from that time forward, nowhere so powerfully than in “The Second Coming.”

THE SECOND COMING Turning and turning in the widening gyre The falcon cannot hear the falconer; Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world, The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere The ceremony of innocence is drowned; The best lack all conviction, while the worst Are full of passionate intensity. Surely some revelation is at hand; Surely the Second Coming is at hand. The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert A shape with lion body and the head of a man, A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun, Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds. The darkness drops again; but now I know That twenty centuries of stony sleep Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle, And what rough beast, its hour come round at last, Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

As Helen Vendler points out in Our Secret Discipline: Yeats and Lyric Form (2007), her very fine close reading of Yeats, “The Second Coming” is a kind of “aborted sonnet,” starting out with an octave with no sestet, before starting a new octave with a sestet—wherein even the rhyme scheme cannot hold. It is also a work of prophecy—but a prophecy of what?

Yeats wrote “The Second Coming” in 1919, when he and his wife were deep into their spiritual research. This was after World War I and at the beginning of the Irish War of Independence, though a few years before the Irish Civil War—so the anxiety so palpable in the poem is more than understandable. But there is no resolution—and there’s not really any hope. An ambivalence haunts the second stanza—what is the sphinx? and what is the rough beast slouching towards Bethlehem to be born? Yeats offers no consolation or closure (which are surely strengths of the poem as a poem) and there doesn’t seem to be a promise of spiritual, let alone societal, renewal… or is there? One thing is clear: the idealism and hope of 1895’s “The Body of the Father Christian Rosencrux” are nowhere to be found.

Yeats, who was not a professing Christian, was nevertheless as haunted by the Druid of Galilee (as my friend Martin Shaw calls him) as anyone, which is only too obvious by his ready citation of scripture and evocation of Bethlehem and the Parousia. Like his fellow magician Dion Fortune, the mystical Christianity rising from the Celtic soil seeped into Yeats’s Celtic soul; and there was no way to extricate it.

There are some things that cannot be resolved or explained. The only consolation to be found is in our capacity to make friends with mystery and to remove our shoes when treading on holy ground. The Otherworld surely exists, but it defies—even laughs at—our attempts, rare as they might be, feeble as they are, to atomize it. Yeats appears to have had at least an intuition of this as early as 1897, as he writes in his story “The Adoration of the Magi”:[2]

“I have turned into a pathway that will lead me from…the Order of the Alchemical Rose. I no longer live an elaborate and haughty life, but seek to lose myself among the prayers and the sorrows of the multitude. I pray best in poor chapels, where frieze coats brush against me as I kneel, and when I pray against the demons I repeat a prayer which was made I know not how many centuries ago to help some poor Gaelic man or woman who suffered with a suffering like mine:—

Seacht b-pádeacha fó seacht

Chuir Muire faoi n-a Mac,

Chuir Brighid faoi n-a brat,

Eidir sinn ’ san Sluagh Sidhe

Eidir sinn ’ san Sluagh Gaoith.

Seven paters seven times,

Send Mary by her Son,

Send Bridget by her mantle,

Send God by His strength,

Between us and the faery host,

Between us and the demons of the air. [1] William Butler Yeats, Essays and Introductions (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1961), 197.

[2] William Butler Yeats, Mythologies (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1959), 315.

The Changing Light at Sandover is one strange poetry collection! I picked up a copy at a used bookstore in DC just after I visited the Exorcist stairs 😂 I think that kind of spirit communication has all kinds of dangers attached to it--but it certainly isn't fake. And I speak from experience. Did you see this version of Fairy Tale from Shane's funeral? Brings a tear. https://youtu.be/6s8lvnSmISc?si=fcS-jeLqawg-jGC_

Among scientists, the belief in materialism as the sole mode of explaining the world is beginning to breakdown. If that belief completely breaks down, I would consider that to be a huge revelation which could effect how we see everything. But really, I don't think the lack of revelation is the problem. 2000 years ago Jesus arrived to lay down the law, and before that, the people had Moses and the prophets. We may be the problem.