I recently finished Ronald Hutton’s book Queens of the Wild: Pagan Goddesses in Christian Europe: An Investigation, published in 2022. Hutton is probably my favorite living historian, writing, as he does, about matters near and dear to my heart, the festival year in medieval and early modern England in particular. Mike Sauter and I interviewed Professor Hutton for the Regeneration Podcast, and I found him to be an open and generous soul, as congenial as he is learned. I’d been reading his books since the mid-1990s, so it was an absolute delight to finally meet him in real time, if not in person.

As with all of Hutton’s books, this one is meticulously researched, fascinating in its conclusions, and honest in its presentation of the facts. He is without a doubt the kind of scholar not captured by ideology. Indeed, much of his argument in the book is about how historians over the last century or so have often been captured or enthused by an idea and whisked away by a hope that something is true, rather than relying on evidence. In this he calls historians such as James Frazer (of The Golden Bough fame), Margaret Murray, and Lady Raglan out on the carpet for letting their enthusiasms outpace their scholarly integrity regarding pre-Christian Europe’s “paganism” and its persistence into the Christian era. Though he doesn’t discuss it much in this book, elsewhere he argues that most of the assumed festivals and rites of neo-paganism are really modern or postmodern iterations of medieval folk Catholicism shorn of Christian imagery and significance. He is not wrong. Not that a lot of neo-pagans are down with this idea.

He is particularly earnest about the assumption among the scholars mentioned above (and contemporary neo-pagans) that much of what persisted in medieval and early modern Western European Catholicism—St. John’s fires, Samhain, and the Twelfth Night “Bean King,” to name a few—are vestiges of pagan religion smuggled into the Christian festival year. Basically, he argues that such claims are not much more than wishful thinking.

I’m glad we got that out of the way.

Queens of the Wild, as is obvious by the title, covers feminine figures from Catholic European folklore ancient or modern, such as Mother Earth, the Fairy Queen, the Lady of the Night, and the Cailleach. For the most part, he argues, they are the product of the modern imagination (from at least from the 16th century, though usually much later). The subtext of the book, then, is that much of the reception of these images in the contemporary West, not only among neo-pagans but in the popular imagination as well, is due to shoddy scholarship (Frazer, Murray, Raglan, et al.) seeping into the greater culture. It’s kind of the folklore version of bad Deconstruction or Judith Butler’s sterile and socially harmful baloney about gender. Once it gets into the culture, it’s almost impossible to get rid of it; and people swear it’s true, even in the face of a complete absence of proof. It’s an “It’s true because I want it to be” deal. And, as anybody can tell from social media, no amount of proof will convince the convicted.

Of course, readers of the Druid certainly know that I consider myself a sort of Catholic Neo-pagan, which is a shorthand way of saying that I maintain a number of medieval and early modern folk Catholic beliefs that are more aligned with contemporary neo-pagans than with most mainline Christians. But I still maintain, with Hutton, that this is an essentially Catholic (archaic though it be) epistemology. Here I stand; I can do no other. (I hope you caught that joke.)

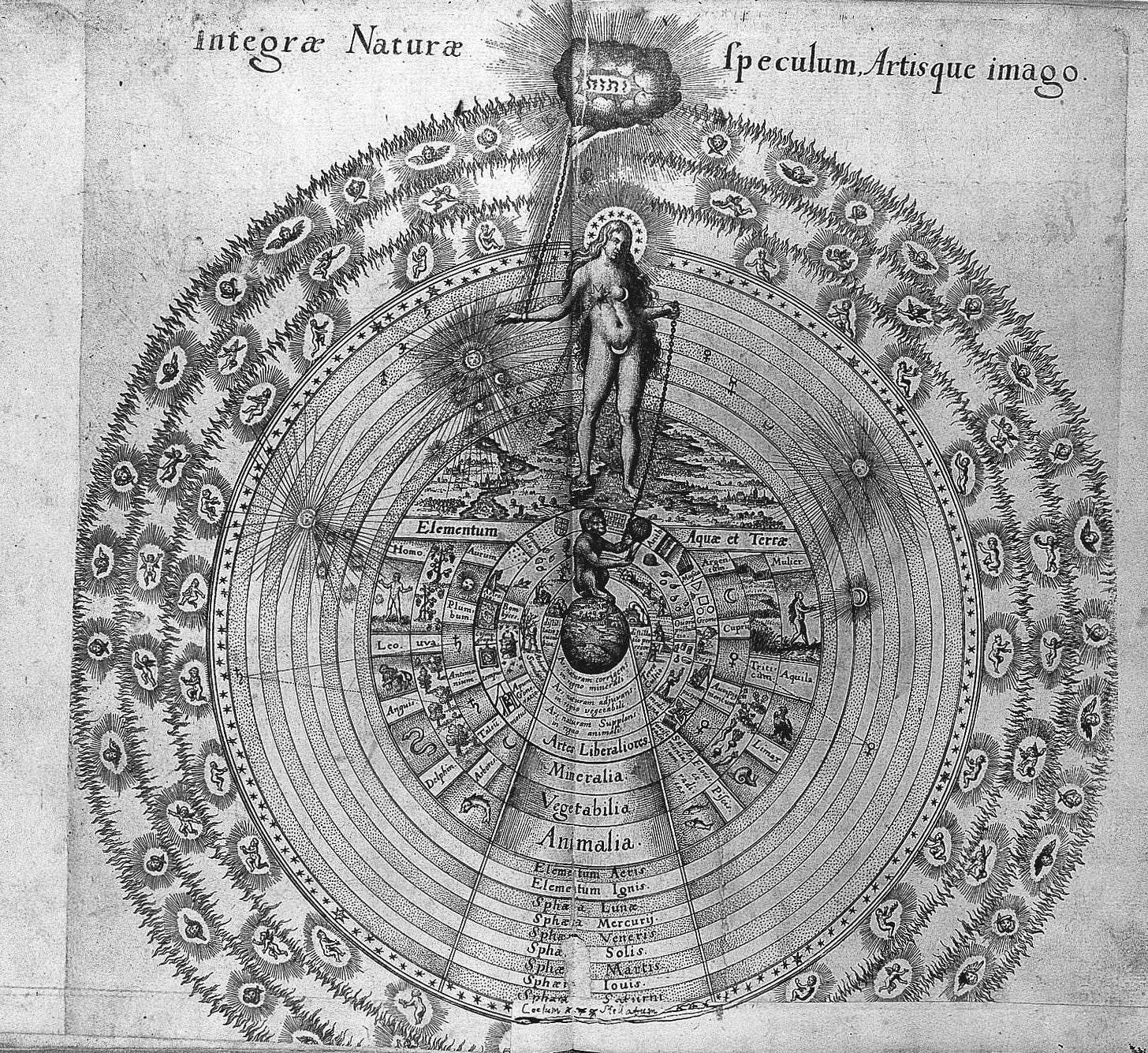

I do have one little problem with Hutton’s book, though. In his chapter on Mother Earth, he cites Robert Fludd’s iconic diagram of the universe. This one:

Hutton identifies the feminine figure here as Mother Earth. Erratum! Actually, she represents the Virgin Sophia, as attested by Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam, Jacob Boehme, and the Rosicrucian tradition to which Fludd belonged among others (like me). No biggie. Everybody makes mistakes.

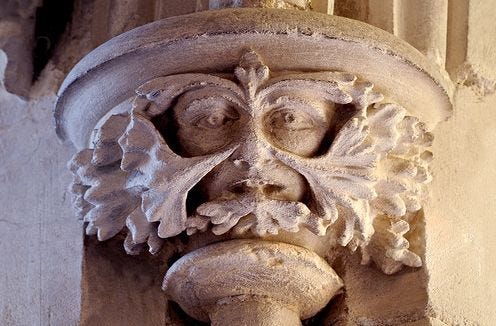

Queens of the Wild, however, includes a 32-page epilogue, entitled “The Green Man,” who didn’t make the starting lineup by not being a feminine figure (note my perceptive scholarly insight). In this epilogue, Hutton excavates the scholarly “consensus” that has prevailed (and continues to be in the popular imagination) that the Green Man seen in the carved foliate heads often adorning churches in Europe. Heads like this one in St. Mary’s Church, Dennington in Suffolk, England:

The scholars Hutton scrutinizes in the book uniformly interpreted such figures as pagan vestiges of the “Old Religion” surreptitiously smuggled into Christian churches as an act of religious subversion. Hutton’s response to such assumptions is somewhere between a scholarly “yeah, right” or a professorial “meh.” Even though scholars have tried to argue that Jack o’ the Green, the Green Knight from the famous Arthurian tale, and even Robin Hood are vestiges of a pagan deity from the Old Religion, he just doesn’t buy it. He doesn’t claim to know exactly what is going on with the green men decorating the sacred precincts of European Christendom, but he sees no reason—and no evidence—to support The Pagan Hypothesis™. And that, ladies and gentlemen, is scholarly humility.

Hutton bases all of his findings on the historical record and archeological evidence; and in those domains he sees no evidence that the Green Man was a pagan deity and counterpart, if not consort, of the Great Goddess. It would be nice if it were true, he seems to imply, but there ain’t no proof.

But here’s the thing: what if someone has seen the Green Man (or, to be more honest, a green man)? As I have written in Sophia in Exile, I saw something (actually several somethings) very like the Green Man when I was in my early-twenties, though I convinced myself my eyes were playing tricks on me. That is, until ten years later when my wife and I were at the Michigan Renaissance Festival and I saw someone in an extraordinary Green Man costume—it was very similar to how the Ents appear in the film version of The Lord of the Rings (though this was long before the films came out) and moved at an agonizingly slow pace. The RenFest version was much larger (about nine feet high) than those I had seen, which travelled along the treetops—also agonizingly slow—but were probably only a foot or two high.

Of course, I don’t know what to conclude about this or how connect it to Hutton’s book. But such things have never stopped me before.

I definitely believe that what I saw was real, and I am sure I am not the only one who has ever seen such things (I would love to talk to that guy in the costume). My assumption is that they were a kind of elemental being, nature spirits; but I would never suggest they were deities. It was more like seeing deer or a rare bird in the woods than an appearance of the Divine.

As for the Green Man carvings in churches, my intuition suggests that the stoneworkers who engraved them were illustrating what St. Hildegard of Bingen called “the greening power of Christ.” They weren’t secret agents of the Old Religion (don’t make me trot out my DaVinci Code screed!), but were Christians who felt the power of Christ working through nature, an insight to which figures from St. Francis of Assisi to Fr. Sergei Bulgakov also arrived. And this, my friends, is an understanding of the world that we would do well to retrieve.

So let me know in the comments what you think; and, if you’ve had experiences of the Green Man (or men), please share them.

Yes, “the past is a different country” This writing brought to mind the book - Motel of the Mysteries where the author did a send up of archaeological interpretations of the past.

https://www.amazon.com/Motel-Mysteries-David-Macaulay/dp/0395284252

The Amazon blurb - “ It is the year 4022; all of the ancient country of Usa has been buried under many feet of detritus from a catastrophe that occurred back in 1985. Imagine, then, the excitement that Howard Carson, an amateur archeologist at best, experienced when in crossing the perimeter of an abandoned excavation site he felt the ground give way beneath him and found himself at the bottom of a shaft, which, judging from the DO NOT DISTURB sign hanging from an archaic doorknob, was clearly the entrance to a still-sealed burial chamber. Carson's incredible discoveries, including the remains of two bodies, one of then on a ceremonial bed facing an altar that appeared to be a means of communicating with the Gods and the other lying in a porcelain sarcophagus in the Inner Chamber, permitted him to piece together the whole fabric of that extraordinary civilization.”

My intuitive hit is that the Green Man is related to Cernunnos, the god of the wild hunt.